Reports of an armed incursion in Russia’s Belgorod region, right on the Ukrainian border, surfaced last week.

In a joint conference, the Freedom of Russia Legion (LSR) and Russian Volunteer Corps (RDK), two paramilitary groups of Russians fighting against Russia on the Ukrainian side, claimed responsibility for the attack, which killed one civilian and prompted the evacuation of nine Russian villages.

They declared their goals had been to “liberate Russia”.

A spokesperson for Ukrainian military intelligence, Andriy Yusov, said that the Belgorod operation was an effort by the LSR and RDK to create a ‘security zone’ inside Russia to protect Ukrainian civilians. He emphasized that only Russian personnel were involved.

Hundreds, and according to some estimates, thousands of Russians are fighting on Ukraine’s side against the Russian armed forces. Most of them are not related to any party or political groupings. But one cohort, and the most public one, draws members from Russia’s far right.

Some of these members of the far right have been serving in the Ukrainian army since 2014, others moved during the “quiet” period in the Donbas conflict or after the full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022. They accuse Russia’s liberal opposition of weakness and describe Vladimir Putin’s regime as a ‘Bolshevik’ one (a term loosely applied to those they disagree with). They see their ideal society in different ways: some agree on a small but Russian republic, others advocate for the restoration of the monarchy.

Even before the start of the conflict in Donbas, Ukraine became a new home for dozens if not hundreds of Russian right-wing radicals persecuted in their homeland. They began to migrate in greater numbers a few years before Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan revolution, in 2009 and 2010, when Russia began to prosecute particularly well-known and radical neo-Nazis. According to some experts, between 2014 and 2019, about 3,000 Russians took part in hostilities on the side of Ukraine.

“Some [of them] had left before,” said Alexander Verkhovsky, director of the Sova Information and Analytical Center, a Russian NGO. “At least since the mid-2000s [which corresponded to a peak of activity for the Russian far right in Russia], there have been a noticeable amount of criminal investigations into [Russian] neo-Nazis. They had reasons to leave [Russia]. Why not go to Ukraine? It was easy to reach, Russian was spoken there and they could find quite a few ‘colleagues’ and settle down.”

The far Right in Ukraine

Alexey “Oswald” Ogurtsov is 29. He grew up in Rybinsk, in Russia’s Yaroslav region. He became interested in nationalist ideas while at school, started doing graffiti and joined street fights with other young far-right sympathizers. He learned martial arts and worked in private security.

In 2010, Ogurtsov was deeply impressed by the riots in Manezhnaya Square in Moscow, which were organized by right-wing football hooligans outraged by the murder of Spartak fan Yegor Sviridov.

He was also very struck by Maidan’s wave of protests and public unrest in Kyiv in 2013 and 2014 and collected money to support protesters. Four years later, he ended up in Kyiv. In a video that appeared on RDK’s official Youtube channel, he claims that he decided to leave Russia because he was being bothered by the Centre for Combating Extremism and the FSB.

Once in Ukraine, Ogurtsov trained with the Georgian Legion but was not sent to fight, as things were relatively quiet between 2018 and 2019. Instead, he began taking part in the actions of Ukrainian far-right nationalist group Tradition and Order.

“I was drawn to everything they did. I liked their action against the gay parade, against the march of transvestites, against feminists and so on,” Ogurtsov said in the RDK video.

On both sides of the war, far-right sympathisers claim they are fighting for the future of Russia.

According to a 2018 report by the NGO Freedom House, far-right groups have been marginal elements in Ukrainian society and politics. They have sought avenues outside of politics to impose their agenda on society, including attempts to disrupt peaceful assemblies and use force against those with opposing political and cultural views. The report does add, however, that since 2014 “extreme nationalist views and groups, along with their preachers and propagandists, have been granted significant legitimacy by the wider society”.

Ogurtsov eventually found a place in the RDK, a paramilitary group set up in August 2022, which brought together Russian fighters from various units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine as well as new Russian recruits.

RDK’s relationship with the Ukrainian army and the country’s intelligence services is not always clear. In October, the group claimed it was performing tasks as part of the 98th territorial defense battalion “Azov-Dnipro” of the Ukrainian army (not to be confused with the volunteer paramilitary group the Azov regiment). But at the same time, the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine informed a Ukrainian outlet, Liga. Novosti, that the RDK was not part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Speaking to openDemocracy, Taras Fedirko, a political anthropologist and researcher of Ukrainian civil society, said: “There is circumstantial evidence that links these Russian groups, as well as different and not very numerous Ukrainian far-right militant groups, to Ukrainian military intelligence (HUR). HUR, and before it (in the war in Donbas) other intelligence agencies, have built relationships with right-wing militants and likely other politicized groups, because they are useful assets: they can be mobilized quickly and flexibly.”

Members of the RDK don’t disclose how many people there are in the group, but it can be estimated at around 100 people. About the same number of right-wing Russians continue to serve in other units, according to Fedirko.

The anthropologist explained there are significantly more Russian passport holders who are fighting on the side of Ukraine who have no links to the far right than those who do.

Commander Rex

The RDK is led by Denis ‘White Rex’ Nikitin (real name Kapustin), a well-known figure in the Russian right-wing milieu.

In the late 2000s, Nikitin created a streetwear brand called White Rex, replete with pagan and neo-Nazi symbols, which sponsored weight-lifting and mixed martial arts (MMA) tournaments. The brand was promoted by Helga Voevodina, the wife of neo-Nazi leader Alexei Voevodin.

Nikitin also expressed support for the Azov regiment, a volunteer paramilitary group created in Ukraine in 2014 to fight pro-Russian forces in the war in Donbas. The unit has drawn controversy over its early and allegedly continuing association with far-right groups and neo-Nazi ideology.

Nikitin moved to Kyiv in 2017 and in August 2020 opened a Telegram channel, in which he posted far-right views.

“The European Union is becoming one big zoo, only there will be whites in cages,” Nikitin wrote in one post.

In August 2022 he launched the RDK and then in a press conference in October explained the group was fighting to defend Ukraine and to defend ethnic Russians within Russia. Over the following months, he gave several long interviews, mostly with YouTube bloggers from Russia and Ukraine.

In a video interview with Russian journalist Oleg Kashin, Nikitin said: “I am faced with the fact that in our wonderful nationalist environment again [they say]: ‘Oh, this is not our war, this is a war of whites against whites’. Boys, what is your war then? Of course, we would all want to serve under swastikas as an army of white Aryans against an army of awful genetic freaks or anti-fascists with big noses and brown skin – and here, blue-eyed blond beasts. But this will never happen. Guys, if this is not your war, your war will never come.”

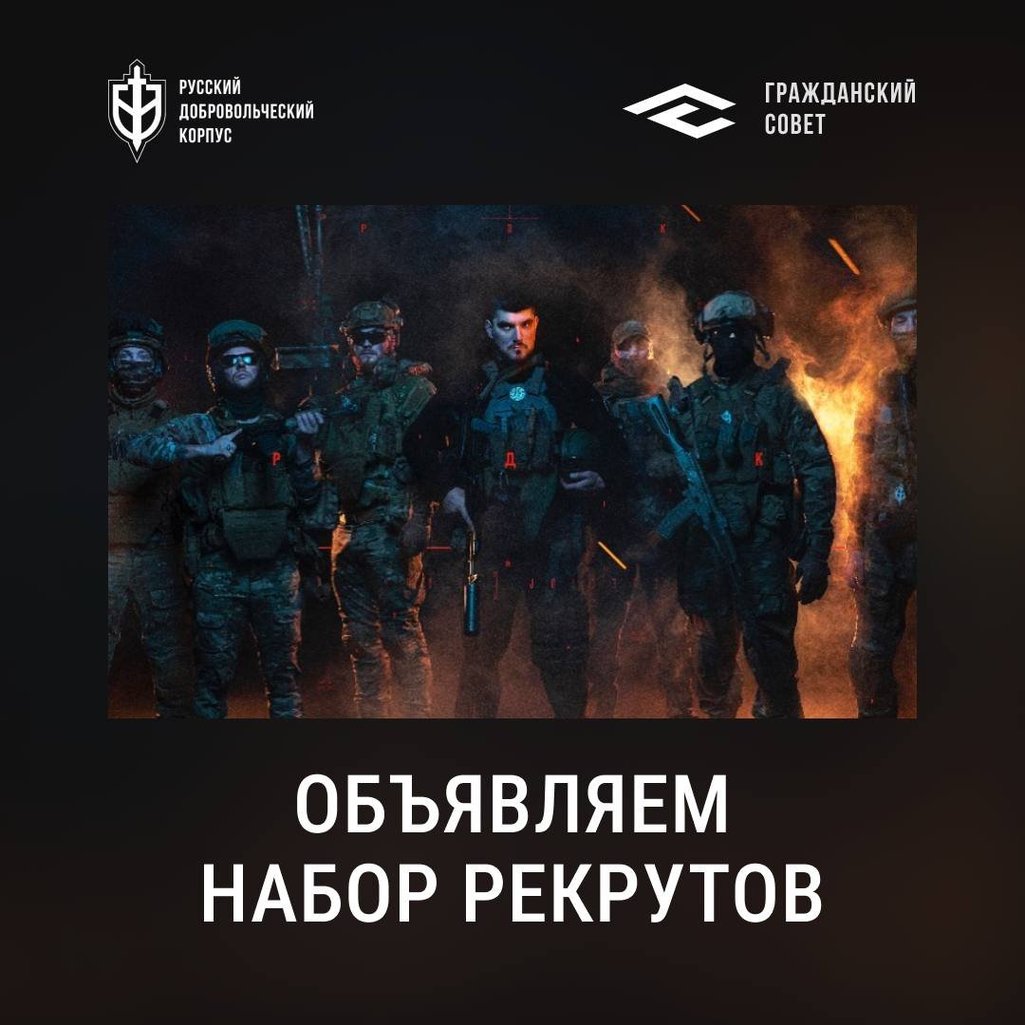

Recruitment ad for RDK taken from the RDK Telegram channel

Conservative-traditional

On 17 May, the RDK announced it would join forces and “come into battle together” with the LSR, another paramilitary group made up of Russians fighting on the Ukrainian side.

Nikitin claims “right-wing conservatives” and “traditionalists” serve in the RDK, and Russians with more centrist leanings join the Freedom of Russia Legion.

Sergey Petrov, who runs Antif.ru, a website monitoring the activity of the Russian far-right on both sides of the front, thinks the RDK’s self-presentation is misleading.

“Just look at the personal [social media] channels of Kapustin and other RDK fighters. These neo-Nazis cannot directly state their views openly, because they are too toxic even in the context of an open armed conflict initiated by Russia under the pretext of ‘denazification’,” Petrov told openDemocracy.

Sleeping cells

The manifesto of the Russian Volunteer Corps is vague when it comes to Russia’s future. It pronounces itself for the return of the annexed territories and the right of nations to self-determination.

Petrov added: “Now the supporters of great Russia, with weapons in their hands, are trying to overthrow the ‘neo-Bolshevik Putin’ in order to establish ‘Russian power’ in their homeland and rid Ukraine of the ‘Asian hordes’. At the same time, they repeat slogans about the inevitable disintegration of Russia into separate regions and are eager to cleanse the remaining ‘Russian lands’ from foreigners. It is useless to look for logic in this, since the ultra-right discourse has always been distinguished by inconsistency.”

Aleksandr Verkhovsky, from the SOVA Center, notes that such slogans are not new and were popular in some right-wing circles even before Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“The idea of ‘Russia for Russians’ could always be implemented in two ways. Firstly, to throw all non-Russians out, or, on the contrary, to create a small territory of only ethnic Russians separated from other territories. This was also actively discussed in the Nineties. Now people from the RDK can afford any political statements, because these are not full-fledged political statements, and they are not a political organization,” Verkhovsky said.

On both sides of the war, far-right sympathizers claim they are fighting for the future of Russia. Those fighting on the Russian side claim they are fighting for Russia not to disappear. Those on the Ukrainian side say they are fighting against a regime that has persecuted them.

In addition to political statements, the RDK claims to have its own sleeper cells in Russia. On 16 May, a video appeared on the corps’ Telegram channel where Nikitin claimed his organization could start a full-fledged armed struggle against the Putin regime from inside Russia.

The video showed five men carrying weapons who compared themselves to the “Primorsky partisans”, a group of young men who in 2010 waged a guerilla war against the Russian police in Primorsky Krai, in the Russian far-east. The video claimed there were already “tens of thousands” of such people inside Russia, but provided no proof.

openDemocracy sent a request to the RDK asking for more information about its political beliefs and views on the future structure of the Russian state. No responses were received at the time of publication.