In March 2020, Italians in quarantine recorded video messages addressed to “themselves of 10 days ago,” before the country went into a national lockdown. The video went viral: a warning to the rest of Europe and the US of what was coming. These ordinary citizens, with names like Anna, Salvatore and Francesca, told us:

A huge mess is about to happen . . . A nice quarantine, the type you only see in movies . . . A whole nation stuck at home. Didn’t see that coming, uh?

I was in Spain, where one of the world’s strictest lockdowns had been enforced days earlier. There were police controls, harsh fines for leaving home without valid reason. No outdoor exercise was allowed; even the kids were shut in. I shared the Italian video with friends in the US and UK, urging them to prepare. “But surely they won’t close the schools,” said one.

That all seems so terribly long ago — a watershed moment captured from the pandemic’s early days. It is something that will help future generations to understand, something to be saved — a digital artifact, now.

As we started to realize that this was going to be a big deal, a collective feeling of living through history kicked in. Museums asked people to save objects of importance, like masks, PPE and gloves. National institutions — the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC, the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London, the National Museum of Singapore and more — launched appeals for pandemic artifacts.

Other museums and community groups were also quick to act. The Vermont Historical Society started to document the outbreak of the virus in Vermont, the Historical Museum of Urahoro, in Hokkaido, Japan, began collecting everyday pandemic-themed objects, Vietnamese artists launched a virtual Covid museum on Facebook. In the UK, the National Archives web team started crawling the Internet for Covid-related terms to capture the government’s response to the pandemic.

Private citizens started to document, too — on social media, in journals and sketchbooks. Awareness that future generations would look back prompted many of us to save objects of everyday importance. They will be stashed in boxes, in attics, and shown to our descendants years later: the mask that Granny wore during the big pandemic, Great Uncle Jeff’s Covid vaccine card.

All around the world, we have been collecting historical relics in real time.

The building blocks of collecting appear relatively simple. Artifacts — physical objects, such as tools and household items, that were made in the past — are gathered by curators.

But this simplicity is deceptive. As Alexandra Lord, chair of the division of medicine and science at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, told me, “Curators are tasked with collecting and documenting and caring for objects that can help us to understand the past.” It’s the assessing and choosing — which objects are relevant, and which are not — that makes curation very tricky. Museum mission statements and collections management policies guide curators as they select, edit, arrange and interpret.

Who collects and what is collected has changed over time. “The traditional museum was composed of collections that they inherited from donors who tended to be elites, who were into travel and collecting objects of curiosity, as they once called them, from the exotic colonial dominion,” says social scientist and curator Kali-Ahset Amen, associate director of the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Nowadays, issues-based museums, tackling topics such as genocide and human rights, have become more prolific, says Amen. They are often story-driven rather than collections-driven. Artifacts may also be digital — oral histories, videos and, of course, social media posts.

Whether a museum is focused on American history, contemporary art or even ice cream, curation is usually shaped by hindsight and knowledge of how a story pans out. But every so often, something so enormous happens that it demands to be documented in real time, collected without hindsight. Something like Covid-19.

Lord’s collecting strategy aims to capture the story of medicine and science in the American nation from the 18th century to the present day. Her team started to think about collecting around the pandemic in late January 2020. By March, it was clear that this was not just a medical story but a global health crisis affecting all aspects of society. Capturing the moment as it happened — collecting diaries, masks, medical scrubs — seemed crucial.

“When Covid hit, what struck me as a medical historian was how much we as a global community have forgotten what it is like to see disease, to see and experience a pandemic and an epidemic as a very real threat,” she says.

Although there have been multiple health crises in recent history, such as the ongoing global HIV/AIDS epidemic, the 2002-04 SARS outbreak and the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, many people — by chance, by privilege — have been in a position to detach themselves, to not feel personally threatened. And the very success of medicine in controlling disease over the last hundred or so years has allowed us to forget what life was like when sickness was ever-present.

But with Covid, “now, all of a sudden, all people were worrying about a disease in a way that people did in the 1880s,” says Lord. And since sooner or later it will happen again, “it is very important to remind people of how people in the past dealt with this.”

Real-time or rapid-response collecting is not easy for curators. The story hasn’t ended yet. And there are so many objects and digital artifacts that could be collected: masks, makeshift PPE, vaccine vials, testing kits, lockdown diaries, sourdough recipes, conspiracy videos, gloves, home-schooling resources.

What is relevant, what is not? What must be saved now? What can be collected later? What do museums have space for?

Lord and her colleagues formed a rapid-response collecting committee to make these decisions and put collecting strategies in place. They consulted other museums, such as the Dittrick Medical History Center in Cleveland and the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. They spoke with contacts at the US Department of Health and Human Services, at the Public Health Service, at libraries and archives. Last spring, the committee was speaking twice a week; now they convene about once a month.

The pandemic had forced many institutions to close their doors, and staff were working from home. There was no one around to take in objects. People submitted offers of objects via email, and choices continue to be made about what to accept: Yes to a nurse’s worn-out shoes and a personalized mask with a slogan on it; no, for now, to objects less centrally relevant. “We’ve asked people to basically hold on to certain objects,” Lord says. “We’re in communication with them. We’ve said, ‘Put this to the side.’”

Establishing a rapid-response network means that submissions can be directed to their best home. An object that tells a story about a local community can be passed to Ohio or Pennsylvania, for example. Something more relevant to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can go to the CDC Museum.

Looking to existing collections also provides insights. The story of polio, for example, helped shape the team’s thinking: “There’s the research angle; there’s the vaccination angle; there’s the individual story of individuals who had polio; there’s the treatment story,” says Lord. Input from colleagues who collected during 9/11 and the HIV/ AIDS epidemic — also in real time — were invaluable. “One of the things that they’ve told us to do is to really focus on the ephemeral, or objects much more likely to disappear,” Lord says.

At the height of the HIV/ AIDS crisis in the United States, curators gathered handmade signs used to protest against the American government’s inaction and the lack of research and treatments. Alongside objects that might quickly disappear, they also collected blocks from the AIDS Quilt, and condoms — which became an important part of the story, Lord notes. “Condoms were marketed, developed, sold as protection and sometimes with public health messages.”

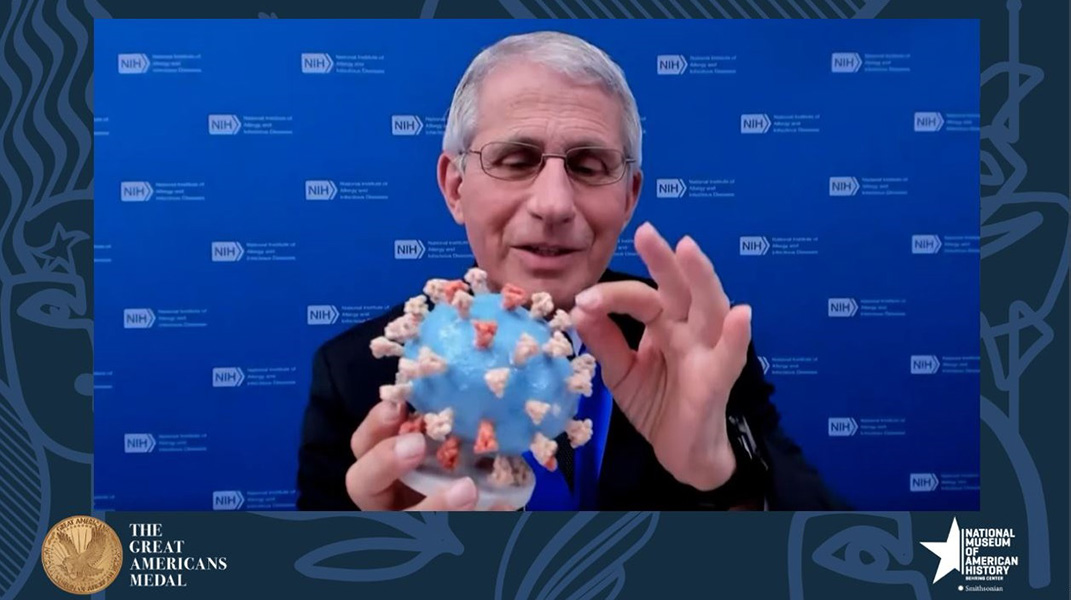

Certain objects are so clearly vital to the Covid-19 story that they have already been couriered to the Smithsonian museum. One is the 3D-printed coronavirus model that Anthony Fauci used to explain SARS-CoV-2 in presentations. Others are the scrubs, vaccination card and empty vial from the first vaccination in the US: that of Sandra Lindsay, a critical care nurse working for the Northwell Health network in New York.

These choices were obvious, but others aren’t. Some things that seem significant at the start of a massive event may prove less so as time goes by — such as, in the case of Covid, the need to avoid touching surfaces. At first, we were told not to touch anything, to wipe everything down, says Lord. “Then, increasingly, it became clear that that was not as worrisome as the aerosol transmission.” Gloves may not prove to be iconic.

Likewise, thermometers. Early on, they were used to detect possible cases of Covid-19. But when it was discovered that asymptomatic carriers, with no elevated temperature, could still spread the disease, their use fizzled out. Even so, Lord spotted the need to collect them — but as representations of an overreliance on technology.

The team is still considering which thermometers to collect, perhaps from testing sites, schools or doctors’ offices. But these can be collected after the fact. Other objects may be lost. Lord is talking with the US Food and Drug Administration’s History Office about collecting fraudulent Covid-19 medicines, items knowingly sold as fake treatments. “It’s highly unlikely we’ll find that in somebody’s attic a hundred years from now,” Lord says — they are flash-in-the-pan objects, important to secure right now before they’re destroyed.

All over the world, curators have been making similar decisions.

In May 2020, the National Museum of Singapore asked the public to submit photos of proposed artifacts online. They have collected photos, as well as various objects, from citizens and organizations: decorative arts, the vial that contained the first vaccine administered in Singapore, sketch journals chronicling people’s thoughts during “circuit breaker,” Singapore’s equivalent of lockdown.

They, too, struggled with knowing what to select in real time, says assistant curator Miriam Yeo: “Will these objects be historically relevant and significant 10 years down the line?” They opted to focus in on items that specifically represent Singapore — including creative work by the Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal Carving Calligraphy & Painting Society. Unable to gather in person, the carvers and calligraphers shared images of their work via WhatsApp. The carved wooden seals have been scanned and compiled in an album named Seals of the Sealed City.

Alongside that album is another seal entitled 口罩背后的微笑 (A Smile Behind the Mask) made by a consultant at the National University Hospital in Singapore. The seal’s design was inspired by a patient’s smile: It shows the Chinese character 笑, for smile, peeping out from behind a surgical mask.

The museum, now reopened, is hosting an exhibition, “Picturing the Pandemic: A Visual Record of Covid-19 in Singapore.” It brings together 272 photographs commissioned from local photographers at the onset of the pandemic, a short film and 16 donated artifacts, including the consultant’s carved seal. The exhibition opened February 27 and runs until August 29.

As the pandemic rolled on, curators began to get a better sense of what would emerge as truly emblematic —and masks were top of the list. They are loaded with meaning and emotion; they have been politicized — weaponized, even. Yet, as Yeo points out, they are also ephemeral. So many are thrown away.

“The kind of surgical masks people wear. They’re mass-produced. You can’t really distinguish one from the next,” she says. “Which do we collect? Do we collect them at all?”

The team in Singapore decided to seek out creative approaches to mask-making and has collected handmade ones, Yeo says. They also gathered a set made by a local fashion brand, YeoMama Batik, which produced the masks from fabric off-cuts.

Masks will also form a significant chunk of the Museum of American History’s Covid-19 collection: high-standard disposable N95 and KN95 masks, but also ones that tell specific stories; masks worn in grocery stores that remained open; masks made by sewing circles for frontline workers; masks printed with cartoon characters and worn by children when they returned to school.

Some people have personalized masks with political messages and funny sayings, says Lord. These are also part of the story. “One of the things that we definitely want people in the future to know and understand is that even in their darkest moments, people have humor about this.”

Though masks are now emblematic, their everyday use came as a shock to those who had not experienced infectious disease crises before. Archival images of mask-wearing and diary entries from the 1918 Spanish flu were shared on social media: Suddenly, they resonated and fascinated.

Oct 17 – They say we may all have to wear “flu” masks. We’d look like members of the “Ku Klux Klan” then.

Oct 21 – No more dates. The girls at the dorm are all quarantined — no influenza there and they think they can keep it out by locking themselves in.

— A “Fluey” Diary, 1918. Montana: The Magazine of Western History 37, no. 2 (1987)

There are obvious reasons why historic comparisons have focused on the 1918 Spanish flu, says Alexandre White, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins. So much was the same: public health interventions, such as masks and quarantines, and the global impact of the pandemic.

Still, he says, there are other, perhaps better models to inform how to collect during Covid-19 — to ensure, in particular, that the actions of local communities are recorded.

White researches the social impact of and global responses to historical and contemporary disease outbreaks — specifically, measures taken to control plague, cholera and yellow fever by International Sanitary Conferences starting in 1851, through to expanded disease controls under the World Health Organization’s 2005 International Health Regulations.

His work examines the perspectives and anxieties of those in power and often relies on imperial archives, such as those collected by the British Library and the Western Cape Archives and Records Service in Cape Town, South Africa. These, he says, reveal the power of the archivist. The story of cholera in India in the 1820s, for example, comes predominantly from a British perspective; the Indian-lived experience of the epidemic is largely absent from the official record.

To White, the 2014-16 Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa represented a kind of turning point. Ethnographers in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea documented the ways in which grassroots efforts — such as contact tracing activities and handwashing stations set up and run by locals — and not solely international aid drove ultimate control of the epidemic.

Careful curation supports such storytelling (curation is more selective than archiving, which aims to comprehensively gather material for future research). Amen of Johns Hopkins was a consulting curator on the CDC’s 2017-18 exhibition “Ebola: People + Public Health + Political Will.” The thinking behind her selection process ensured that the voices of all players in the narrative were captured. To find artifacts, she spent two months in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea. “The essence, really, is to first of all be aware of the fact that collecting is not a politically neutral project,” she says.

Her initial remit from the CDC was to collect items such as residual medical supplies and the oral accounts of international health workers on the ground. But she immediately extended her strategy. The story of international help in tough conditions was valid but — as a sociologist by training — she wanted to capture a more complicated narrative, one that had multiple players. Through her lens, the Ebola response comprised a network of “social actors,” each with different resources and perspectives. She went in asking, “Who’s got what, who’s doing what, and then what are the grassroots responses to those actions?”

She spoke with international NGOs and foreign medical practitioners and public health experts. But — really importantly, she says — she sought out and met informal and formal community groups, such as an association of Sierra Leonean market women. She collected items such as public health signage, leaflets and protective suits, but looked to the less obvious, too. Ebola, for example, threatened the market women’s livelihoods. To tell the story of how they kept the market open, Amen collected examples of the partitions they used to control entry, exit and movement in the space to ensure that customers felt safe.

Artifacts such as a local gravedigger’s pickax and magical objects made by traditional healers — fashioned, as Amen says, “to try to cast out the spirit of Ebola from the village” — further build a history that captures the interplay of international and local efforts in the Ebola response and recovery.

Both Amen and White believe that there are lessons to be learned from West Africa, both in terms of dealing with highly infectious disease outbreaks and in capturing the story of Covid-19. White hopes that Covid-19 collecting will similarly reflect the importance of grassroots efforts, especially in the absence of significant federal responses in, for example, the US. People delivering groceries to the vulnerable and those at risk, shut-down restaurants pivoting to become small grocery stores — “It’s been the actions of local community members that have, I think, in many ways helped this epidemic in the US from not being worse,” he says.

Amen says that Covid-19 collections will enable historical comparisons and show “certain human tendencies that will rear their heads with each pandemic.” Skepticism and doubt about the vaccine and the very existence of the disease have run rife during Covid-19, along with resistance to following the guidance of public health experts. “All of those same variables were present in West Africa in the Ebola time,” she says.

In an age where everybody is questioning facts, Amen adds, absolute transparency will be key to telling the story of Covid-19 — transparency around how collections were formed and interpreted, in how knowledge was produced. “It’s a creative act,” she says. “We are producing it and we’ve made certain decisions in the process, and we need to not be opaque about that.”

Perhaps as never before, citizens are also trying their hand at this creative act of curation. Covid-19 is being documented, edited, arranged and displayed online, in real time, 24-7. We have filled Instagram, Facebook and Twitter with #stayathome and #vaccinated images and commentary; we make audio journals and videos. Posts of our vaccination days, TikToks by Gen-Zers in lockdown, “Plandemic” YouTube videos: Everyone is an amateur archivist now. “What’s really interesting to me about this event is that people are very conscious of documenting and recording,” says Lord.

But, she adds, people have always been aware of when they are living in extraordinary moments. It was true even back in the time of the Black Death, whose aftermath led to an obsession with mortality: “The idea of the memento mori, the reminder of death, the idea of using a skull as a reminder that death is ever present, death is right around the corner.”

White also flags other digital records as invaluable. For more than a year, people have been meeting on Zoom — for family get-togethers, birthday parties, Thanksgiving meals. Many of these have been recorded, and the archive is important. “I think that makes this epidemic unique in human history, to some extent, because of the ways we’re isolated but closer, in different ways,” he says.

Most poignantly, these include Zoom calls to dying family members, and funerals. White notes that these raise important ethical questions around collecting. “Private moments of epidemics are often very brutal and very sad and very personal,” he says. “It invites the question of what should be made visible and what shouldn’t.”

Some acts of recording this moment are extremely deliberate and visible. Artists and designers have been prolific throughout; creative work is already being curated and shown. In Singapore, the National Museum’s online exhibition #NeverBeforeSG, curated by Yang Derong and launched in October 2020, shows Covid-19 works by 87 artists and designers, including photography, interactive games, verse and fashion designs.

In the UK, design historians Anna Talley and Fleur Elkerton created the Design in Quarantine project, with the V&A and the Royal College of Art. The online platform collates design responses to the pandemic from around the globe. They are grouped in loose categories and randomly displayed on the home page. “We’re really mindful that we didn’t really want to input too much structure and opinion onto a collection that was forming in real time and happening around us,” Elkerton says.

Yet the garments, posters, digital designs and other artifacts displayed here do express emerging narratives: closeness while isolated, the importance of community and social media, the complex meanings of emblematic objects such as masks.

Walking Stick, designed by the Center for Optimism, Clara Meister and Sam Chermayeff, is a simple piece of wood. It is six feet long and has a brass ring handle at each end. “The idea is that you would go out for a walk with a friend and you would each hold one end of the walking stick,” says Talley. Socially distanced yet connected. “Usually when you have a walking stick, it’s to support you as an individual when you go for a walk, but this one is really supporting two individuals in that process.”

Another submission is by artist B Gowtham of Chennai, India: He used papier mâché and recycled plastic bottles to create a corona helmet and Covid-19 auto rickshaw. In the early days of the pandemic, Gowtham drove around in that rickshaw to draw attention to the threat of the virus.

And in Nairobi, Kenya, hairdresser Sharon Refa created a coronavirus hairstyle for kids using green and pink threads that mimic the coronavirus molecule spike. It is a fun hairstyle, says Elkerton, but one, like Gowtham’s creation, with intention. “She knew that she could help spread awareness on her local community level of the virus, of what to do, of being aware that it was spreading.”

Talley, who has a background in graphics, points to global similarities in the signage and posters used in public health outreach for Covid and for other epidemics. When information needs to be conveyed across different languages in different countries, for example, bold symbols are used, such as the cross in tuberculosis posters. “It’s the same thing with the coronavirus,” she says. “We have this sort of spiky ball logo that we see everywhere.”

Lord does not know exactly when staff will return to the Museum of American History, but they are getting ready. Her division, of medicine and science, has now received several hundred offers of objects and narrowed it down, for now, to fewer than one hundred — those that are most relevant and can best be cared for. Her team is providing instructions: how to pack objects, how to formally gift them to the museum. By fall, she thinks, the first objects from ordinary Americans will start to arrive.

She expects to be collecting around Covid-19 for the rest of her career. Thirty years from now, she says, people rummaging around in their parents’ homes will find objects related to the pandemic and will contact the museum. “I would even argue a hundred years from now, going through your grandmother’s attic, you will find these objects and write to us,” she says.

We do not know how this story ends. But, ultimately, how we remember these times — what goes in the history books, what we teach in the future, what humanity learns — will all be shaped by what is collected and captured right now.

I replay the Italian video on YouTube and try to remember March 2020.

You’ll start seeing beauty and ugliness together…. You’ll live moments of unity you would’ve never imagined.

A digital artifact, now. I am remembering and thinking: They were right.

This article is part of Reset: The Science of Crisis & Recovery, an ongoing series exploring how the world is navigating the coronavirus pandemic, its consequences and the way forward. Reset is supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.