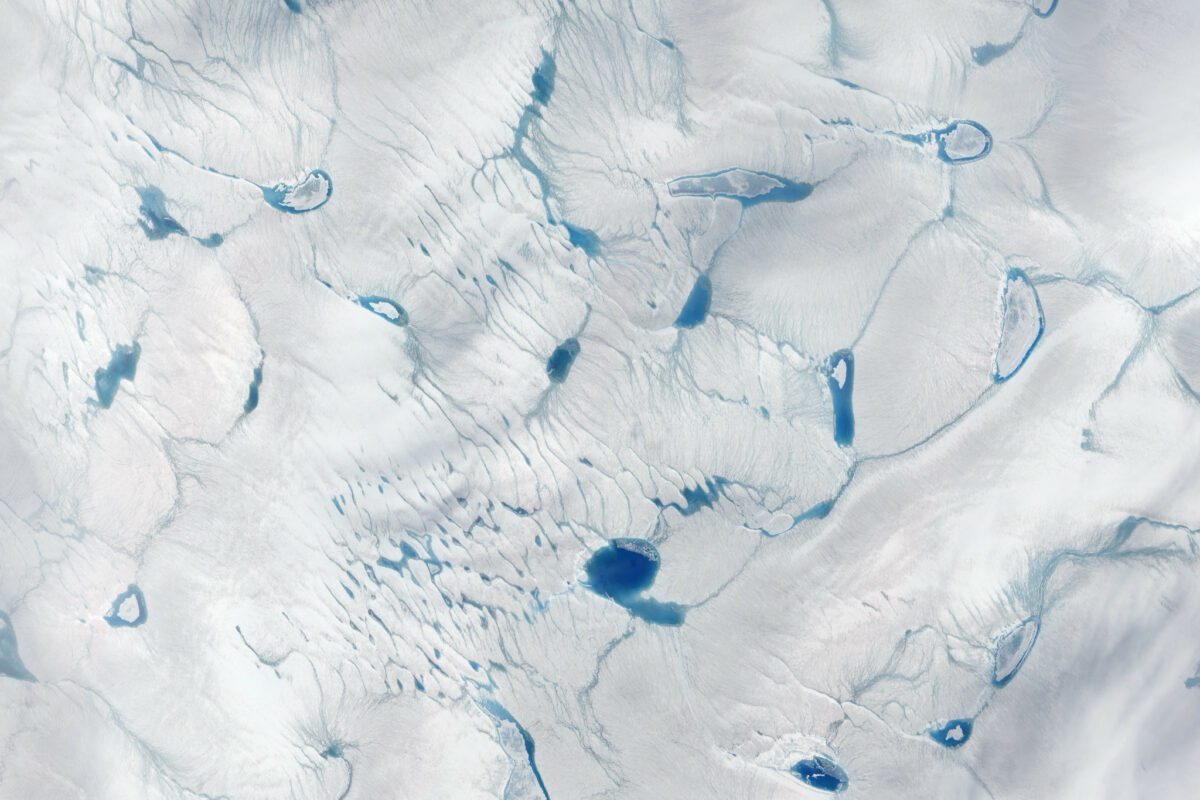

The fossil fuel-driven climate emergency has already locked in so much ice melt in Greenland that sea levels will surge by nearly a foot in the coming decades, peer-reviewed research published Monday warns, underscoring the need to rapidly transform virtually all aspects of the global political economy.

Even if the world stopped emitting greenhouse gases today, the Greenland ice sheet is set to lose at least 3.3% of its mass, or 110 trillion tons of ice, and that will cause almost a foot in global sea-level rise (SLR), says the study, published in Nature Climate Change. The authors don’t specify a time frame for the melting and SLR, though they expect much of it to happen between now and 2100.

But rather than lead to despair, this projection of inevitable damage—made by scientists based at institutions in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United States—should catalyze immediate and robust climate action, experts stress. Without it, the life-threatening situation confronting humanity is destined to grow far deadlier.

Earlier this year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted that sea levels along the U.S. coastline would rise by an average of 10 to 12 inches by 2050, drastically increasing the threat of flooding in dozens of highly populated cities.

By mid-century, 150 million people worldwide could be displaced from their homes just by rising sea levels, according to some estimates. The consequences of a one-foot SLR would be especially catastrophic for developing island nations, where low elevation and high poverty combine to increase vulnerability.

These countries, which have done little to cause the climate crisis now roasting the Greenland ice sheet, lack the financial resources for adaptation and face the prospect of being wiped off the map.

“Every study has bigger numbers than the last,” William Colgan, a scientist at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland and co-author of the new paper, told The Washington Post. “It’s always faster than forecast.”

As lead author Jason Box, also from the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, told the newspaper, the finding that 3.3% of Greenland’s ice sheet will be gone in a matter of decades regardless of what is done to halt planet-heating pollution represents “a minimum, a lower bound.”

Things are all but guaranteed to get worse if humanity continues to burn fossil fuels. Should the record-breaking ice loss that occurred in 2012 become the norm, for example, the world is likely to see around two-and-a-half feet of SLR from Greenland alone, the study says.

By the same token, each fraction of a degree of warming that is avoided makes a difference.

If Greenland’s ice sheet were to disintegrate completely, sea levels would rise more than 22 feet—”enough to double the frequency of storm-surge flooding in many of the world’s largest coastal cities” by the end of the century, scientists have warned, so the stakes for adequate climate action are still immense even if a certain amount of melting and SLR has been deemed irreversible.

Greenland is located in the Arctic, which has been heating up for over a century and is one of the fastest-warming regions in the world. Dangerous feedback loops are of particular concern. The replacement of reflective sea ice with dark ocean water leads to greater absorption of solar energy, and the thawing of permafrost portends the release of additional carbon dioxide and methane—both leading to accelerated temperature rise that triggers further melting, defrosting, and destabilization.

In December, researchers estimated that the Arctic has been heating up four times faster than the rest of the globe over the past three decades. Another recent study found that 2021 was the 25th consecutive year in which Greenland’s ice sheet lost more mass during the melting season than it gained during the winter. Rainfall is now projected to become more common in the Arctic than snowfall decades sooner than previously expected.

This context has a direct bearing on the new paper, which contains more dire predictions than other reports relying on different assumptions.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), for instance, has projected that Greenland will lose roughly 1.8% of its mass and contribute up to half a foot of SLR by 2100 if humans continue spewing large amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

“One reason that new research appears worse than other findings may just be that it is simpler,” the Post explains. “It tries to calculate how much ice Greenland must lose as it recalibrates to a warmer climate.”

“In the past, scientists have tried to determine what Greenland’s ongoing melting means for the global sea level through complex computer simulations,” the newspaper continues. “They model the ice itself, the ocean around it, and the future climate based on different trajectories of emissions.” The result, in general, has been “less alarming predictions.”

As the Post reports:

The new research “obtains numbers that are high compared to other studies,” said Sophie Nowicki, an expert on Greenland at the University at Buffalo who contributed to the IPCC report. Nowicki observed, however, that one reason the number is so high is that the study considers only the last 20 years—which have seen strong warming—as the current climate to which the ice sheet is now adjusting. Taking a 40-year period would yield a lower result, Nowicki said.

[…]

Box, for his part, argues that the models upon which the IPCC report is based are “like a facsimile of reality,” without enough detail to reflect how Greenland is really changing. Those computer models have sparked considerable controversy recently, with one research group charging they do not adequately track Greenland’s current, high levels of ice loss.

For example, the processes causing ice loss from large glaciers in Greenland “often occur hundreds of meters below the sea surface in narrow fjords, where warm water can flick at the submerged ice in complex motions,” the newspaper notes. “In some cases, these processes may simply be playing out at too small a scale for the models to capture.”

Pennsylvania State University professor Richard Alley, an ice sheet expert who was not involved in the study, told the Post that “the problems are deeply challenging, will not be solved by wishful thinking, and have not yet been solved by business-as-usual.”

One thing that’s certain, Alley added, is that higher temperatures will lead to greater amounts of SLR.

“[The] rise can be a little less than usual projections, or a little more, or a lot more, but not a lot less,” he said.