Last month, the World Bank announced that it would suspend new lending to Uganda in light of the country passing its Anti-Homosexuality Act, which the bank said “fundamentally contradicts our values”.

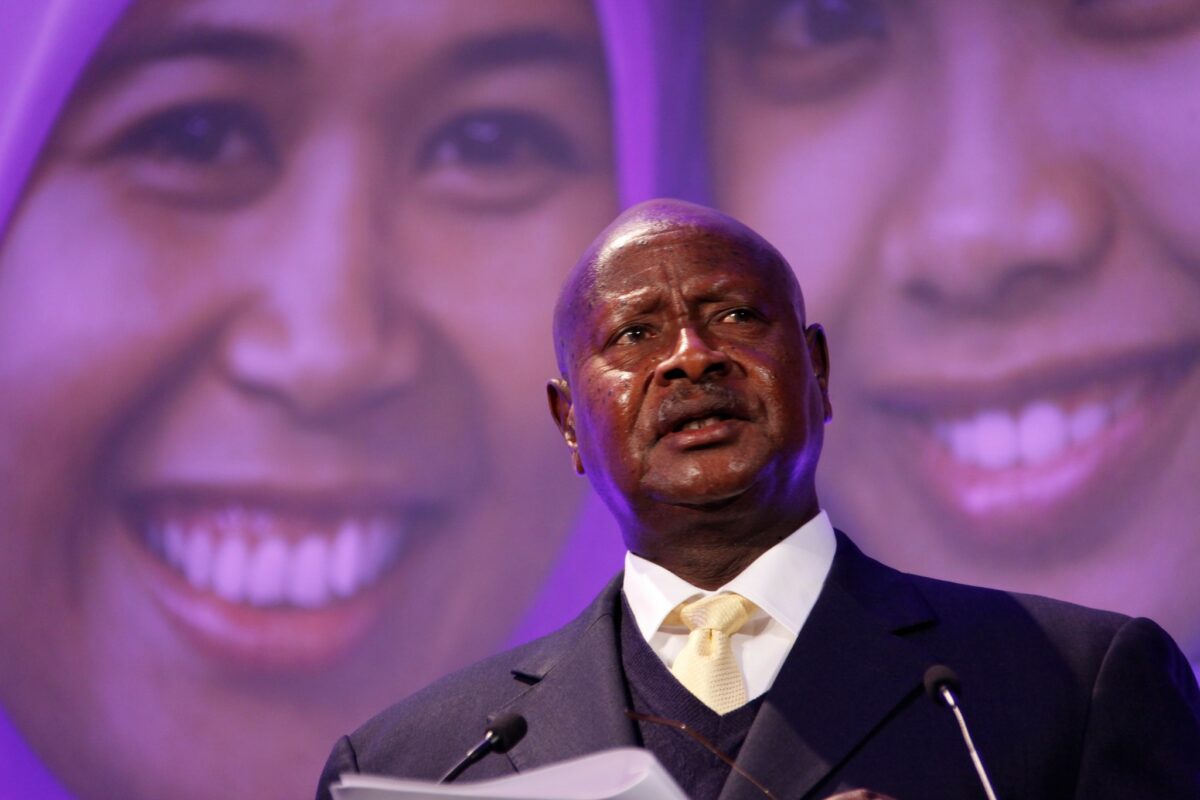

In response, president Yoweri Museveni accused the bank on X (formerly Twitter) of coercing Uganda into “abandoning our faith, culture, principles and sovereignty using money”. and claiming that the country “will develop with or without loans”.

It’s true that the World Bank’s decision will likely have little effect on the political elite who passed the bill. But ordinary Ugandans will suffer, particularly the queer people that the bank seems to be advocating for.

The bank is the country’s biggest lender. By the end of the 2021/22 financial year, 34.5% of Uganda’s public debt was owed to the bank.

As of December 2022, the World Bank – through its member organisation the International Development Association (IDA) – had earmarked $5.4bn in loans and grants for disbursement to Uganda. The funding has gone to a variety of projects: supporting smallholder farmers, women entrepreneurs, refugees, infrastructural development, and health facilities providing services including HIV/AIDS care and maternal health services.

The bank’s action last week does not automatically mean existing projects will stop – but there will be “no new public financing to Uganda”.

Uganda’s economy is already under strain, recovering from the effects of Covid, and navigating the economic effects of the war in Ukraine. Millions struggle to afford daily life because of a sustained rise in food prices and essential household items.

The trickle-down effect of this lending cut will exacerbate things for the average Ugandan, including LGBTIQ people and other vulnerable groups.

Unemployment and systematic exclusion from health services are some of the most common challenges faced by queer people in the country, largely owing to state-sponsored homophobia. For instance, LGBTIQ people suffer a disproportionately high prevalence of HIV infection compared to the general public: 13% for men who have sex with men, and over 20% for trans women, compared to 6.2% of the general population aged between 15 and 64.

These dire statistics are surely linked to stigma in medical care and a lack of training and knowledge on gender and sexual diversity for health professionals, driven by the criminalisation of homosexuality.

If the World Bank is trying to advocate for queer people, then pushing them further into poverty while withholding life-saving healthcare, infrastructural and entrepreneurial support hardly seems the way to do it.

Museveni’s response and counter-accusations

At all levels of power, between government and its opposition, the World Bank’s decision has spurred an imperialist blame game – and LGBTIQ Ugandans are once again caught in the middle.

On the government’s part, Museveni insisted in an online statement: “We do not need pressure from anybody to know how to solve problems in our society. They are our problems.”

The president has repeatedly framed anti-gay legislation as some organic effort by Ugandans to “solve” the “problem” of homosexuality, and international opposition as opprobrium for these efforts. But in reality, homophobia – especially the kind that seeks to legalise death for homosexuals – is far from a native exercise.

Museveni has openly associated with Western anti-rights individuals and groups who have been linked to the political organising that preceded Uganda’s 2014 and 2023 anti-homosexuality laws.

David Bahati, then the MP who introduced the 2014 bill in Uganda’s parliament, said he had been inspired by the Fellowship Foundation (also known as the Family) – an influential US conservative group whose ‘National Prayer Breakfast’ lobbying event has been replicated in various countries around the world, including Uganda. A 2020 openDemocracy investigation found that the Family spent more than $20m in Africa between 2008 and 2019, with more than 80% of this going to its projects in Uganda.

The official opposition is little better. Robert Kyagulanyi (also known as Bobi Wine), the leader of the National Unity Platform, tweeted in response to the World Bank’s announcement: “It’s disturbing how institutions like these ones give priority to only gay rights and ignore all the other gross human rights violations… Dear @WorldBank, all human rights are human rights!”

But Wine has never criticised the anti-homosexuality bill as a violation of human rights. Even as LGBTIQ people face life imprisonment and death, Wine appears to maintain the position that both the ruling government pushing for the persecution of queer people, and the international bodies that speak against it, are deflecting from more important issues.

All but one MP from Museveni’s National Resistance Movement party voted to pass the bill in May. So did every MP from Wine’s party.

The World Bank decision is the real distraction

In a political atmosphere firmly united behind legalising the death of queer Ugandans, leaning on powerful Western-backed institutions to penalise the Ugandan political elite for their homophobic projects may seem like an attractive option, perhaps even the only viable one for queer organisers.

Up to 150 civil society organisations around the world – including some from Uganda – called on the World Bank “to stop current and future lending to Uganda” until the law is overturned by the constitutional court, where a petition challenging it is currently being heard. In LGBTIQ circles in Uganda, the decision has been widely hailed.

But it is not the solution we need.

By focusing on the result – legalised homophobia in Uganda – and not the cause, which is the financial and ideological overreach of Western anti-rights groups, the World Bank’s decision is fundamentally flawed. The same white supremacist, Western-centric ideology that protects Global North anti-rights actors spreading hate in Africa also supports blanket sanctions that seek to kill and impoverish those who suffer their influences in the Global South.

Homophobia, from colonial-era laws to present-day ones, are largely a Western product

The World Bank’s decision actively distracts from conversations and efforts by many African rights organisers who have long traced and identified US and European anti-rights groups as the root of these laws, and called for them to be sanctioned. Focusing only on their African acolytes gives these groups the opportunity to keep organising – meaning we will likely see a repeat of this cycle in a few years even if the court strikes down the current law, as it did the 2014 one.

Real international allyship with queer Africans is going to take much more than lipstick-on-a-pig kinds of decisions – and, as I wrote here last month, more than imperialistic finger-wagging. But that is only an argument for why the World Bank decision is harmful. What of its efficacy?

Indiscriminate sanctions championed by the West are often designed with the end goal of forcing or “inspiring” regime change in authoritarian states, but they have famously underdelivered on this, while markedly increasing poverty and suffering among civilians and ordinary citizens. There is no reason to believe that this will be different for Uganda.

For African queer organisers, there are no easy answers, but perhaps we should consider the famous words of Audre Lorde: the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.

Homophobia, from colonial-era laws to present-day ones, is largely a Western product. This is the house the West built.