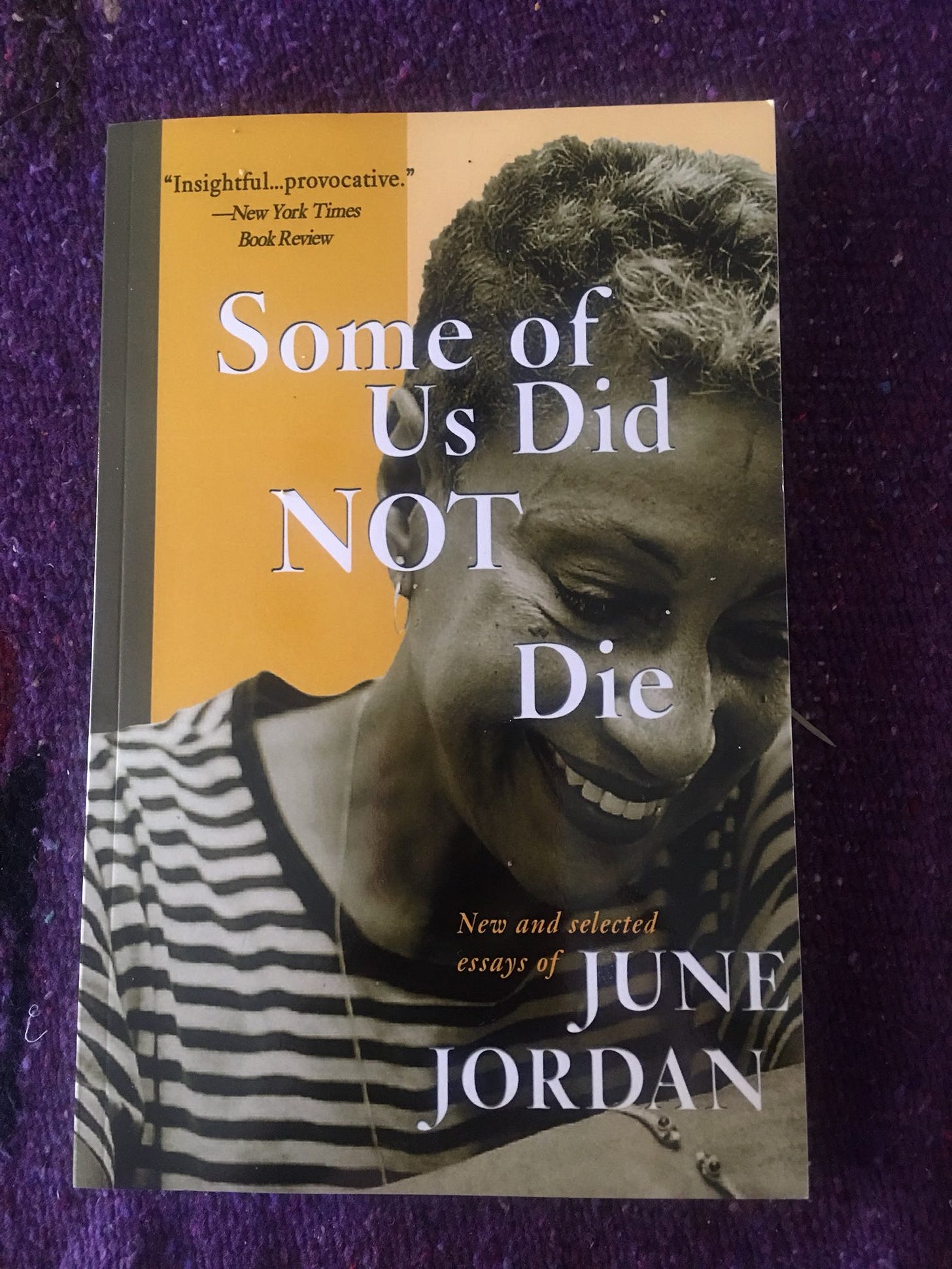

“I realized that regardless of the tragedy, regardless of the grief, regardless of the monstrous challenge, Some of Us Have Not Died. Some of us did NOT die…And what shall we do, we who did not die?” the poet and activist June Jordan asked in a keynote presentation at Barnard College on November 9, 2001. It has been adapted as Some of Us Did Not Die, the title of an essay and an anthology of her essays.

Her questions were about the September 11 attacks, less than two months before her talk. In examining how those who survived can best honour those killed, June Jordan quotes Holocaust survivor Elly Gross: “I guess it was my destiny to live…To live means you owe something big to those whose lives are taken away from them.”

“What shall we do now? How shall we grieve, and cry out loud, and face down despair?” Jordan asks. They are questions that are just as urgent today, in the midst of the worst pandemic in a century, when the death toll in the United States alone is 200 times that of 9/11 and multiples more across the world where at least 3.5 million have died so far.