Why is Ross Douthat? Or Maureen Dowd? Or Frank Bruni or Gail Collins or Bret Stephens or Thomas Friedman or… just… why… is The New York Times opinion section?

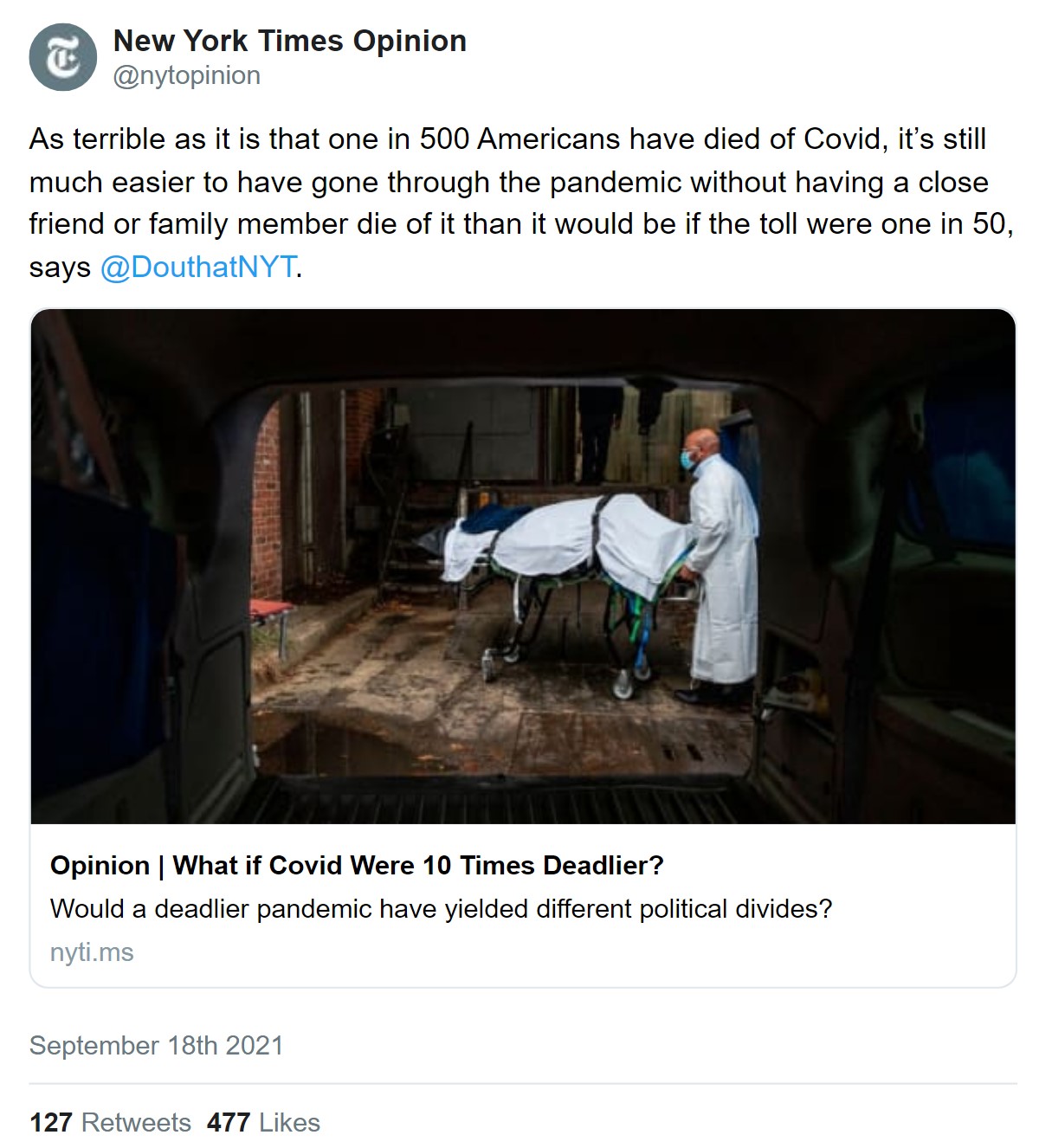

Now, you might say, “Hey! Those aren’t actual questions, or even sentences, for that matter” — and I’d have to concede those points, fair enough. But it’s rare that a day goes by without seeing a terrible piece of rage-bait being released into the wild by one of the Times’s big name opinion-slingers, leading me to ask… “WHYYYYYYY?” Earlier this year, Douthat dropped what may very well be the best of the worst of this media genre: a “What If…” style thought experiment.

It was, and I kid you not, that while Covid-19 is bad… a disease that was 10 times worse would be, well, worse.

That’s it! As a country, we’re more than 2/3 of the way to a million dead bodies because of this disease, but the man who once wrote about his encounter with a woman resembling “a chunkier Reese Witherspoon” waded into the world of relativism for the sake of a thought experiment about suffering and politics.

I’m not going to go point by point through Douthat’s essay because it’s honestly not worth the time or energy. It’s just an exercise in relative privation. On its own, the piece fails to make a coherent argument. Would the politics of Covid been worse or better if the virus was 10 times deadlier? I don’t know, mostly because the death toll in the current pandemic continues to rise.

He wraps the piece up by pointing out that “one thing we don’t seem to be doing yet is preparing for the next pandemic” (this is an important point!), but then immediately closes it by saying that we may one day experience a worse pandemic. Would this have made a fine blog post? Sure. Or maybe a newsletter? Absolutely. But the fact that Douthat’s piece was published in the actual, physical Sunday edition of the paper says a lot about what kind of lazy writing gets rewarded with lucrative jobs with the type of retention usually reserved for Supreme Court justices.

Let’s face it. This is not a Ross Douthat problem, this is an industry problem.

In the world of media, few jobs are as prestigious as that of the opinion columnist. Sure, a paper’s editorial board might provide the paper’s official point of view on a given topic, but it’s the individual opinion columnists whose names and faces get plastered across the pages and whose views get echoed across other mediums such as TV and radio. Opinion columnists at legacy media institutions are the closest things newspapers have to bona fide celebrities on staff. They shape the discourse and influence the world around them.

That said, it’s time for newspapers to reevaluate how they run their opinion sections, beginning with something akin to “term limits” for the paper’s individual staff columnists.

Too much time in the world of opinion journalism can melt one’s brain. (See: The New York Times’s David Brooks.)

I was only four years old when David Brooks first took a job as a columnist. I am 35 now. In other words, he’s been at this for a while.

Brooks’s career has seen him at The Wall Street Journal, The Weekly Standard, and since 2003, The New York Times. Before I get too far into this, I’d like to note that I am using Brooks as an example in this piece not because he is an outlier, but because he’s not. Everything about him is so perfectly average — a replacement-level conservative scribe, much like Douthat but lighter on the religious angles.

In July 2017, Brooks used his column to tell a bizarre and condescending story about “a friend with only a high school degree” who was utterly baffled by fancy sandwiches:

Recently I took a friend with only a high school degree to lunch. Insensitively, I led her into a gourmet sandwich shop. Suddenly I saw her face freeze up as she was confronted with sandwiches named “Padrino” and “Pomodoro” and ingredients like soppressata, capicollo and a striata baguette. I quickly asked her if she wanted to go somewhere else and she anxiously nodded yes and we ate Mexican.

American upper-middle-class culture (where the opportunities are) is now laced with cultural signifiers that are completely illegible unless you happen to have grown up in this class. They play on the normal human fear of humiliation and exclusion. Their chief message is, “You are not welcome here.”

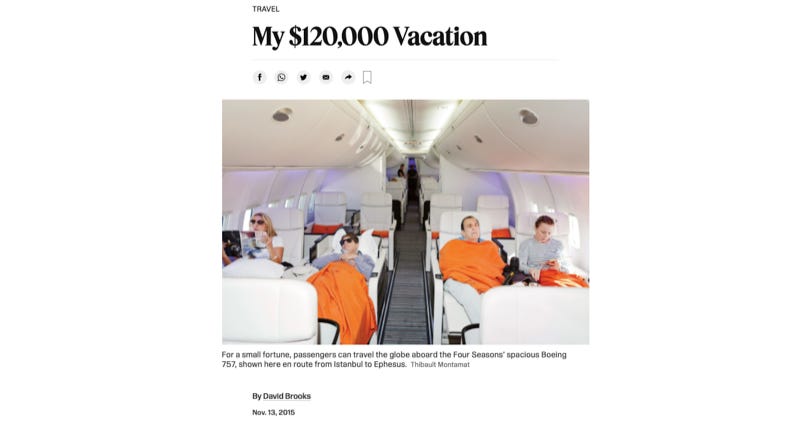

I tried but failed to ward off the second bottle of champagne. I was sitting in my room at the Four Seasons Hotel Istanbul at Sultanahmet, on the phone with a friend. The hotel staff had already brought me chocolates and Turkish delight to welcome me. They’d put bookmarks in the books I’d left on the desk. They’d replaced my bathmat midday because I’d gotten the first one wet. They’d arranged my notes for this article in clean little stacks. There was already one ice-bucketed bottle of champagne on the dining room table when the door chime rang.

In January 2014, Brooks addressed income inequality by demonstrating just how little he understands about the issue. He slams it as “needlessly polariz[ing],” and offers up right-wing pablum about this being a matter of social and cultural problems that people bring on themselves.

There is a very strong correlation between single motherhood and low social mobility. There is a very strong correlation between high school dropout rates and low mobility. There is a strong correlation between the fraying of social fabric and low economic mobility. There is a strong correlation between de-industrialization and low social mobility. It is also true that many men, especially young men, are engaging in behaviors that damage their long-term earning prospects; much more than comparable women.

Low income is the outcome of these interrelated problems, but it is not the problem. To say it is the problem is to confuse cause and effect. To say it is the problem is to give yourself a pass from exploring the complex and morally fraught social and cultural roots of the problem. It is to give yourself permission to ignore the parts that are uncomfortable to talk about but that are really the inescapable core of the thing.

At the core of many of Brooks’s bad column ideas is a belief that his gut instinct or assumption about a given issue is simply a fact. For instance, in February 2012, he wrote a column about NBA player Jeremy Lin in which he made the bold (and extremely false) claim that religious people are rare in the world of pro sports.

Jeremy Lin is anomalous in all sorts of ways. He’s a Harvard grad in the N.B.A., an Asian-American man in professional sports. But we shouldn’t neglect the biggest anomaly. He’s a religious person in professional sports.

We’ve become accustomed to the faith-driven athlete and coach, from Billy Sunday to Tim Tebow. But we shouldn’t forget how problematic this is. The moral ethos of sport is in tension with the moral ethos of faith, whether Jewish, Christian or Muslim.

Columnists are victims of their own success, which is all but guaranteed. Brooks has, like many in the professional opinion set, lost touch with reality the longer he’s held the job. His columns often touch on the issues of the day or a look at what politics means to the average, everyday American, though he is not an average, everyday American.

It’s not his fault that he isn’t the prototypical American news consumer. In fact, it’s only because he’s been so successful that he’s achieved such rarefied status in the first place. It’s also what’s made so much of his work utterly unreadable.

This happens a lot in other industries as well. For instance, if a comedian’s success was built on how relatable their observational jokes were, massive success means that they may eventually stop being so relatable to their audiences, at which point they can either shift their style along the way or try to fake relatability that once came naturally. Over time, it just gets harder to fake it. (see: Jerry Seinfeld)

The same is true for columnists. Sure, there are exceptions, but columnists whose success was built on telling personal stories will eventually find themselves woefully out of touch with readers. This is how you end up with stories about a person being confused by a fancy sandwich and the internal politics of Barack Obama’s birthday party guest list, as Maureen Dowd did just last month.

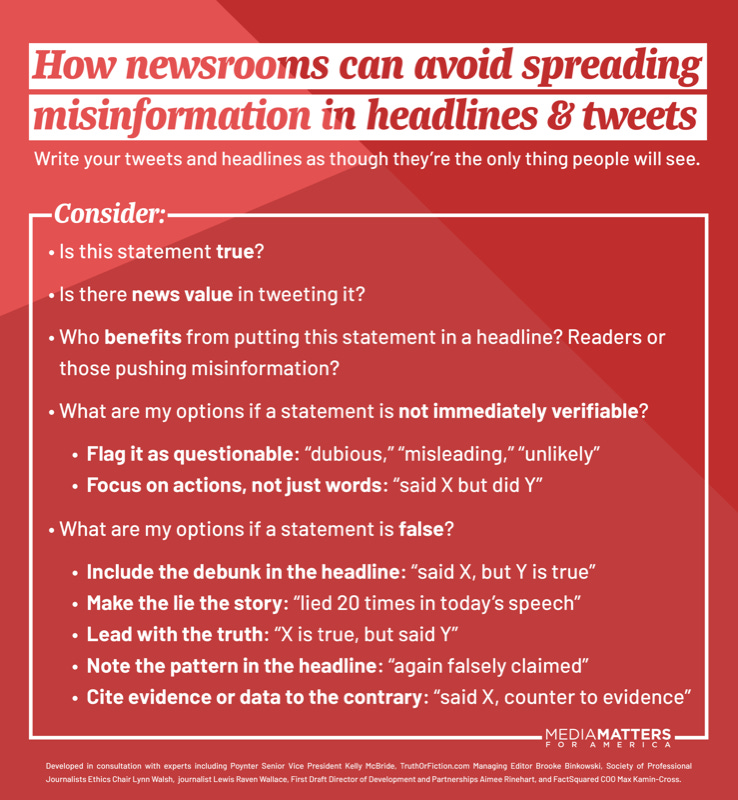

Average people struggle to differentiate between news and opinion, and newspapers have a responsibility to address this. One of my biggest passion projects over the past few years has been an effort to improve headlines and the text that gets posted to social media sites. During my time at Media Matters, I co-wrote a guide to fixing “broken” headlines.

The headline problem is just one of many in the world of journalism. The overwhelming majority of people who see an article cross their Twitter timeline will not click it. This is true of both news and opinion, and it contributes to distrust of the press. But rather than make substantive changes that might help lend credibility to the press as a whole, the industry seems set on superficial changes like “retiring the term ‘op-ed’” and tweaking the font used for opinion articles.

Those changes are welcome (the font change, especially, as it was an effort to distinguish the paper’s reporting from the paper’s opinion pieces), but it’s time for elite, financially stable newspapers to make an even bigger change.

To start: it’s time to place 5-year limits on individual columnists.

How does the public benefit from Brooks’s diatribes about fancy sandwiches, Thomas Friedman’s secondhand stories from cab drivers, or Bret Stephens’s tendency to churn out poorly-researched pieces in which he compares online critics of his to Nazis?

It really does seem as though the longer columnists retain their gigs, the less meaningful output they seem to have. They are not experts in any particular field, but rather, generalists who often run out of useful ideas. This is how you end up with contrarianism for contrarianism’s sake and stories about sandwiches. After five years on the job, swap them out with fresh faces.

There’s something about the fact that in the aftermath of 9/11, two separate Times columnists published takes that included the line, “Give war a chance.” There’s zero accountability in the world of opinion journalism. If there was, the same people who cheered the U.S. into war in Afghanistan wouldn’t be the ones popping up in newspapers and TV now to lecture the public on what they think is the right thing to do right now.

Newspapers could do themselves a big favor by cutting back on columnists overall and investing in informed outside opinions.

Remember when Stephens used his column at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic to roll his eyes at the idea of people being asked to take precautions as the virus began spreading across the country?

No wonder so much of America has dwindling sympathy with the idea of prolonging lockdown conditions much further. The curves are flattening; hospital systems haven’t come close to being overwhelmed; Americans have adapted to new etiquettes of social distancing. Many of the worst Covid outbreaks outside New York (such as at Chicago’s Cook County Jail or the Smithfield Foods processing plant in Sioux Falls, S.D.) have specific causes that can be addressed without population-wide lockdowns.

Yet Americans are being told they must still play by New York rules — with all the hardships they entail — despite having neither New York’s living conditions nor New York’s health outcomes. This is bad medicine, misguided public policy, and horrible politics.

Who benefitted from that piece, from Stephens loudly declaring that “the rest of America needs to get back to life”? For all the great work the paper does when it comes to its reporting, trotting out highly-paid generalists like Stephens to shout his uninformed opinion to the world only serves to undermine it. Maybe this makes business sense, but it does the public a disservice.

Opinion journalism can be wonderful, but when columnists lose touch with readers and fail to provide factually sound content, we are all left worse off. If newspapers must have opinion sections (another issue that I may one day write about), there’s no valid reason not to strive for a substantive, factual discussion centered around a collection of experts. This is especially true when it comes to things like public health, climate change, and the other challenges that face us.

But as long as places like the Times continue to allow columnists to stay on staff to the point of brain rot, the public is going to continue to be force-fed repetitive nonsense about controversies on college campuses and personal grudges.