In 2022, an AI-generated work of art won the Colorado State Fair’s art competition. The artist, Jason Allen, had used Midjourney – a generative AI system trained on art scraped from the internet – to create the piece. The process was far from fully automated: Allen went through some 900 iterations over 80 hours to create and refine his submission.

Yet his use of AI to win the art competition triggered a heated backlash online, with one Twitter user claiming, “We’re watching the death of artistry unfold right before our eyes.”

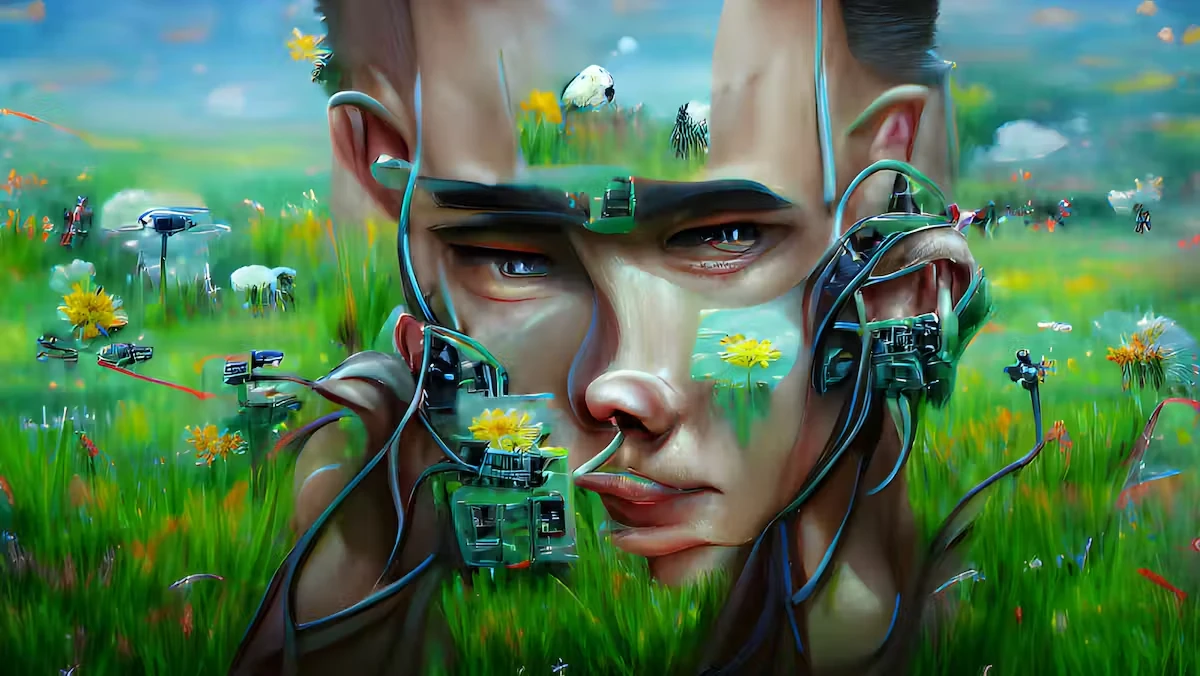

As generative AI art tools like Midjourney and Stable Diffusion have been thrust into the limelight, so too have questions about ownership and authorship.

These tools’ generative ability is the result of training them with scores of prior artworks, from which the AI learns how to create artistic outputs.

Should the artists whose art was scraped to train the models be compensated? Who owns the images that AI systems produce? Is the process of fine-tuning prompts for generative AI a form of authentic creative expression?

On one hand, technophiles rave over work like Allen’s. But on the other, many working artists consider the use of their art to train AI to be exploitative.

We’re part of a team of 14 experts across disciplines that just published a paper on generative AI in Science magazine. In it, we explore how advances in AI will affect creative work, aesthetics and the media. One of the key questions that emerged has to do with U.S. copyright laws, and whether they can adequately deal with the unique challenges of generative AI.

Copyright laws were created to promote the arts and creative thinking. But the rise of generative AI has complicated existing notions of authorship.

Generative AI might seem unprecedented, but history can act as a guide. Take the emergence of photography in the 1800s. Before its invention, artists could only try to portray the world through drawing, painting or sculpture. Suddenly, reality could be captured in a flash using a camera and chemicals.

As with generative AI, many argued that photography lacked artistic merit. In 1884, the U.S. Supreme Court weighed in on the issue and found that cameras served as tools that an artist could use to give an idea visible form; the “masterminds” behind the cameras, the court ruled, should own the photographs they create.

From then on, photography evolved into its own art form and even sparked new abstract artistic movements.

Unlike inanimate cameras, AI possesses capabilities – like the ability to convert basic instructions into impressive artistic works – that make it prone to anthropomorphization. Even the term “artificial intelligence” encourages people to think that these systems have humanlike intent or even self-awareness.

This led some people to wonder whether AI systems can be “owners.” But the U.S. Copyright Office has stated unequivocally that only humans can hold copyrights.

So who can claim ownership of images produced by AI? Is it the artists whose images were used to train the systems? The users who type in prompts to create images? Or the people who build the AI systems?

Unlike inanimate cameras, AI possesses capabilities – like the ability to convert basic instructions into impressive artistic works – that make it prone to anthropomorphization. Even the term “artificial intelligence” encourages people to think that these systems have humanlike intent or even self-awareness.

This led some people to wonder whether AI systems can be “owners.” But the U.S. Copyright Office has stated unequivocally that only humans can hold copyrights.

So who can claim ownership of images produced by AI? Is it the artists whose images were used to train the systems? The users who type in prompts to create images? Or the people who build the AI systems?

While artists draw obliquely from past works that have educated and inspired them in order to create, generative AI relies on training data to produce outputs.

This training data consists of prior artworks, many of which are protected by copyright law and which have been collected without artists’ knowledge or consent. Using art in this way might violate copyright law even before the AI generates a new work.

For Jason Allen to create his award-winning art, Midjourney was trained on 100 million prior works.

Was that a form of infringement? Or was it a new form of “fair use,” a legal doctrine that permits the unlicensed use of protected works if they’re sufficiently transformed into something new?

While AI systems do not contain literal copies of the training data, they do sometimes manage to recreate works from the training data, complicating this legal analysis.

Will contemporary copyright law favor end users and companies over the artists whose content is in the training data?

To mitigate this concern, some scholars propose new regulations to protect and compensate artists whose work is used for training. These proposals include a right for artists to opt out of their data’s being used for generative AI or a way to automatically compensate artists when their work is used to train an AI.

Training data, however, is only part of the process. Frequently, artists who use generative AI tools go through many rounds of revision to refine their prompts, which suggests a degree of originality.

Answering the question of who should own the outputs requires looking into the contributions of all those involved in the generative AI supply chain.

The legal analysis is easier when an output is different from works in the training data. In this case, whoever prompted the AI to produce the output appears to be the default owner.

However, copyright law requires meaningful creative input – a standard satisfied by clicking the shutter button on a camera. It remains unclear how courts will decide what this means for the use of generative AI. Is composing and refining a prompt enough?

Matters are more complicated when outputs resemble works in the training data. If the resemblance is based only on general style or content, it is unlikely to violate copyright, because style is not copyrightable.

The illustrator Hollie Mengert encountered this issue firsthand when her unique style was mimicked by generative AI engines in a way that did not capture what, in her eyes, made her work unique. Meanwhile, the singer Grimes embraced the tech, “open-sourcing” her voice and encouraging fans to create songs in her style using generative AI.

If an output contains major elements from a work in the training data, it might infringe on that work’s copyright. Recently, the Supreme Court ruled that Andy Warhol’s drawing of a photograph was not permitted by fair use. That means that using AI to just change the style of a work – say, from a photo to an illustration – is not enough to claim ownership over the modified output.

While copyright law tends to favor an all-or-nothing approach, scholars at Harvard Law School have proposed new models of joint ownership that allow artists to gain some rights in outputs that resemble their works.

In many ways, generative AI is yet another creative tool that allows a new group of people access to image-making, just like cameras, paintbrushes or Adobe Photoshop. But a key difference is this new set of tools relies explicitly on training data, and therefore creative contributions cannot easily be traced back to a single artist.

The ways in which existing laws are interpreted or reformed – and whether generative AI is appropriately treated as the tool it is – will have real consequences for the future of creative expression.