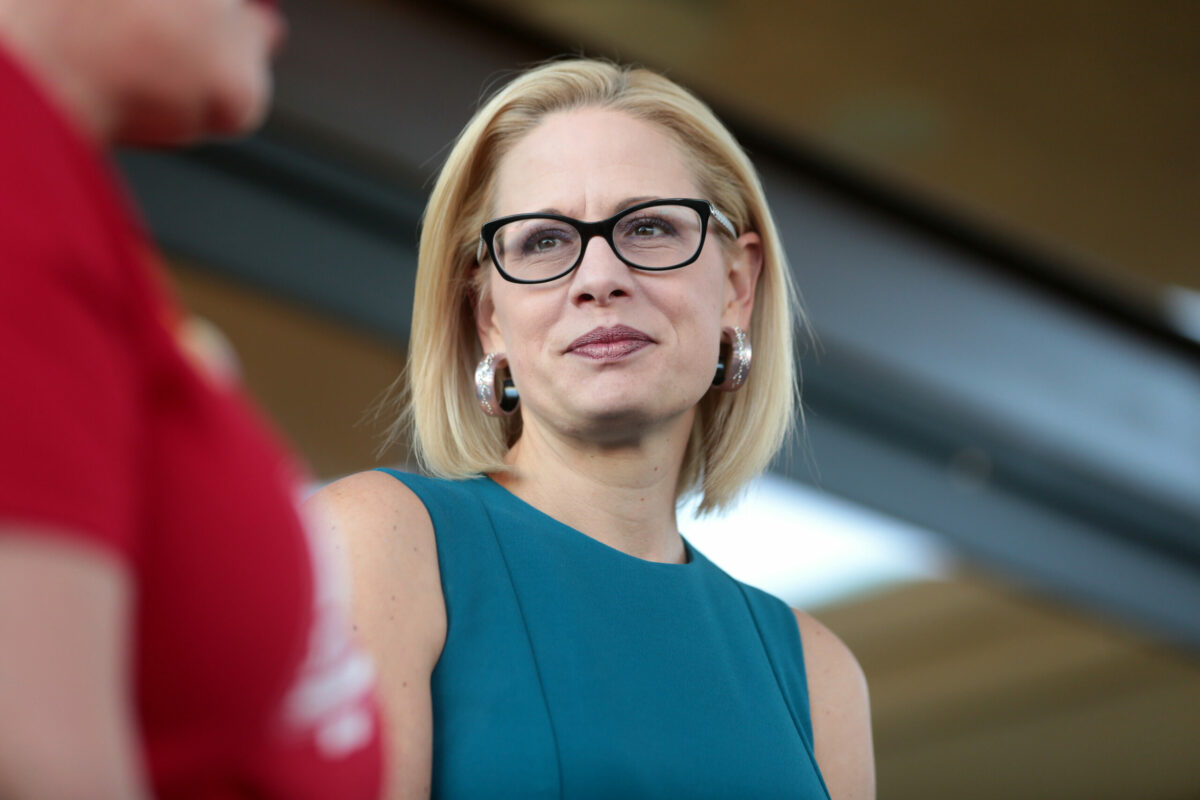

When Sen. Kyrsten Sinema walked onto the Senate floor in March to vote against the inclusion of a minimum-wage hike in President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill, the “no” vote itself didn’t come as much of a surprise.

The first-term Democratic U.S. senator from Arizona had signaled that she believed a wage increase should be considered on its own, not as part of the pandemic package, and promised she would “keep working with colleagues in both parties” to make it happen.

But the flair with which 44-year-old Sinema, a triathlete with a penchant for vibrantly hued wigs, voted to reject the proposal stunned progressives already wary about whether she had their backs.

After showing up for the vote carrying a chocolate cake, Sinema entered the chamber, walked to the front, paused, formed a thumbs down — a gesture often used by voting senators — and curtsied.

The backlash was swift.

“Just wow,” Rep. Mark Pocan, a Wisconsin progressive, wrote on Twitter, linking to a 2014 post from Sinema calling to raise the minimum wage.

“No one should ever be this happy to vote against uplifting people out of poverty,” Rep. Rashida Tlaib, a Michigan Democrat and “squad” member, wrote later that day, linking to a video clip.

The Huffington Post reported that Sinema was facing criticism for an “exaggerated thumbs-down hand gesture.” The Washington Post referred to Sinema’s “combustible thumb.” A Tucson Sentinel columnist called it the “curtsy heard ‘round the world.” An Arizona Republic columnist said that rather than grant people a living wage, Sinema “would rather they eat cake.” Within a couple of weeks, the liberal magazine The Nation published what it called the “origin story of the Senate’s newest super villain.”

Sinema said nothing publicly. Her office told the Huffington Post that “commentary about a female senator’s body language, clothing, or physical demeanor does not belong in a serious media outlet.”

A spokesperson did tell an Arizona newspaper that the cake was for Senate staffers who had worked overnight. But neither the senator nor her office explained the rest: The much-dissected curtsy was not a comment on the minimum wage but rather Sinema acknowledging the nonpartisan staffers, who had read aloud the 628-page COVID-19 relief bill at a Republican senator’s request and who were thanking her for the cake as she voted, according to those in the Senate that day.

With a cake and a curtsy — and little explanation — Sinema’s transformation into a super villain to the left was complete.

In 2018, Sinema, a former state lawmaker and member of the U.S. House of Representatives, was the first woman Arizona had elected to the Senate and the first Democrat in 30 years. She had years before, as a member of the minority party in the state house, decided she needed to tone down her “bomb thrower” image to get things done. For a time she succeeded, though some of the resulting political victories were short-lived.

Now, Sinema and West Virginia’s Joe Manchin are critical moderate votes in an evenly split Senate, and Democrats need both to pass key pieces of President Joe Biden’s agenda, including infrastructure and care packages, and a sweeping voting-rights bill for which Sinema was an original cosponsor. In this political climate, it is becoming increasingly unclear whether Sinema’s continued desire to hear from her Republican colleagues, but not explain herself to her more liberal constituents, is the best way to achieve the kind of durable change she has sought during her political career.

Manchin and Sinema are also the only outspoken Democratic holdouts for scrapping the filibuster, a procedural hurdle that effectively requires 60 votes to pass most pieces of major legislation. With Republican Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s recent statement that he is “100 percent” focused “on stopping” Biden priorities, chances for bipartisan success seem slim.

David Lujan, a Democrat who served with Sinema in the statehouse representing their Phoenix-area district, said in an interview last month that the senator is as “politically astute as anybody.” If he had to pick one issue that might bring her around to changing the filibuster, it would be the voting-rights bill she cosponsored. “If she realizes that there’s just no way to compromise, I think she will consider: What are the other options to be able to get [this] done?” he said.

But the little she’s said recently doesn’t make that look likely. When the Arizona Republic asked Sinema about the filibuster in a rare interview last week, she told them that senators need to “get out of their comfort zones” and build bipartisan coalitions because that is the way “lasting things get done.”

“The reality is that legislation that stands the test of time is created through both bipartisanship and compromise,” she added.

One place Sinema has explained herself is in her 2009 book on coalition building. In it, the one-time Code Pink anti-war activist described her first year in the state legislature as a “bust” and “just plain sad,” because she accomplished so little. In her second year, she cast aside her liberal “bomb thrower” persona. Sinema wrote that “the bomb thrower has made a choice —whether consciously or not— to be excluded from the actual process of negotiating.”

In her book, Sinema details a series of resulting political victories that include defeating one ballot proposition to prohibit same-sex marriage and preventing another from making it onto the ballot that would have banned affirmative action. But those victories were short lived: Versions of both were subsequently approved by Arizona voters, revealing the fragility of the coalitions that she helped build to initially defeat them.

The U.S. Senate in 2021 is a different playing field than the U.S. House of Representatives in 2013, and more different still than Arizona’s state House and Senate in 2005 and 2011, respectively. The first four months of this year are the only time in Sinema’s 16 years in public office that she has been a part of the political majority. Her continued focus on building coalitions with Republicans, without showing signs of recalibration, have Arizona progressives worried Sinema is now poised to throw bombs at her own party’s priorities.

To gain insight into Sinema’s thinking, The 19th spoke to nearly two dozen individuals who are either friends with the senator, worked with her in the state legislature or in Congress or during her campaigns, or belong to key constituency groups that hope to bend her ear.

Like super villains, Washington politicians have origin stories. Sinema’s is about a woman who has always had her eye on the next step. Along the way, she was a political outsider who became an insider, and a rabble-rouser activist who became a centrist lawmaker.

She was born in the late 1970s in Tucson to an attorney father and a stay-at-home mother, a middle child with an older brother and a younger sister, in a family that started out solidly middle class and belonged to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Sinema’s father lost his job in the 1980s recession. Her parents divorced, and Sinema’s mother subsequently married an educator at her elementary school. They moved shortly thereafter to her stepfather’s hometown of Defuniak Springs, Florida.

The family had a rocky start in the rural Panhandle town, where the population in 1980 was roughly 5,500. They lived in an abandoned 864-square foot gas station without traditional plumbing owned by her stepfather’s parents. Sinema has spoken openly about how during this period, she qualified for free school lunches and the family’s diet was supplemented by church food pantries. Once her stepfather secured a job with the local school district, their fortunes began to shift. In 1987, a local Mormon bishop helped Sinema’s parents secure a $100,000 mortgage for a nearby farmhouse.

Sinema excelled as a student. She graduated early from high school and then from Brigham Young University (BYU), where she earned a degree in social work.

Sinema returned to Arizona in 1995 to begin her career, but “dissatisfaction set in almost immediately,” she wrote. “I kept asking myself, ‘Couldn’t I have a larger impact —couldn’t I make a difference in the underlying structure that created this vicious cycle of poverty?’”

Sinema went to night school, earning a master’s degree in social work from Arizona State University. But by 2002, she said, she had “really hit a wall.” A friend suggested she go to law school and run for office, which she did.

She finished last in a crowded field in her first run for the Arizona House, as a Green Party-affiliated independent. She joined the Democratic Party and was elected in 2004, earning a law degree that same year from Arizona State University. In 2010, she was elected to the state Senate, and in 2012 she earned a doctorate in justice studies.

These years in the state house are the focus of Sinema’s book, which reads like a political self-help manual. After her first year as a “crusader for justice, a patron saint of lost causes,” she decided she was “done with the fiery rhetoric” and decided to make friends with political opponents. The word “friend” appears 64 times in Sinema’s book, including a chapter with the title, “Making Friends.” It nearly always applies to her colleagues on the other side of the aisle.

Though Sinema frequently refers to herself as a progressive, she writes about others who identify by the same title with some derision, saying as a group they make “great victims.” In warning about how liberal advocacy groups can “take themselves too seriously” she describes how, “if you’re not wearing all-hemp clothing, listening to Cat Stevens, and making your own paper and soy ink, you’re not welcome” in their coalitions.

It is clear, in the book, that Sinema believes one of her most significant political victories — in its result and in her methods — is her work helping lead the Arizona Together coalition to defeat a 2006 ballot proposition to amend the state constitution to prohibit marriage equality.

She urges fellow progressives to “put down those shiny plastic binders, store away the charts and graphs” of research and take a page from conservatives and use “values language” to advance arguments. Sinema describes how, once the coalition learned the best way to tank the ballot measure would be to focus on how unmarried heterosexual couples could also lose benefits, and not civil liberties for LGBTQ+ couples, they traveled the state “road-show fashion, to share our early research findings with activists.”

“I still get angry e-mails from some members of the LGBT community” about the approach, Sinema writes.

The ballot measure failed in 2006. But success was not complete: Voters approved a narrower version in 2008.

Sinema is the first out bisexual person elected to Congress, and though she was open about her sexuality during her congressional campaigns and accepted support from LGBTQ+ groups, she has been prickly when asked about it. “I don’t think this is relevant or significant. I’m confused when these questions come up,” she told the Washington Post shortly after her 2012 House election.

“I don’t think that’s any of your business,” she told Elle magazine of her dating life later that year in a profile that said she had never married. The Arizona Republic reported during her Senate campaign that Sinema was in fact married to a man she met at BYU for an unknown duration.

Her reticence has extended to her religious beliefs. Though she left the Mormon church sometime after college graduation, and was sworn into Congress with her hand on a copy of the U.S. Constitution, Sinema told the Washington Post in early 2013 that she had “great respect for the LDS church — their commitment to family and taking care of each other is exemplary.”

Sinema had not always avoided talking about her early years. But, when she ran for Senate, the details of her story were scrutinized in news coverage that questioned whether her childhood was as hardscrabble as she made it seem. Sinema’s communications team put out a four-page document with decades-old details that included a copy of her mother’s bank statement. It noted Arizona’s definition of homelessness including living in a building that was not intended to be a residence for a human being. Sinema has made herself less accessible to the news media ever since.

Sinema’s office ignored all but one of a dozen requests made by The 19th to interview the senator in Washington, or in Arizona, or by phone or email. They likewise declined to make a member of her staff available to discuss her policy priorities or respond to points that would be made in this story. “I am sorry we missed you,” a spokesperson eventually replied when The 19th traveled to Arizona during an in-state work period last month.

Among those who have worked with Sinema, two descriptors that cropped up more than once were “enigma” and “mystery.” Some described her as an “authentic” progressive who “has a strong heart.”

“I don’t think she’s changed her views on any of the issues, I just think she has changed her approach,” one person said.

Others thought she engaged in “performative bipartisanship” and “triangulates every single thing she does.” She “doesn’t care what [Democrats think]” because she “sees her voters as independents and crossovers,” another concluded.

Who is, and isn’t, able to get an audience with Sinema has become the subject of much discussion in Arizona’s political circles.

Trish Muir, the chair of the Pima Area Labor Federation, a local council of the AFL-CIO in the Tucson area, which is historically home to Arizona’s Democratic base, said that the federation’s members “are not just liberal Democrats” and from “all walks and all political beliefs” but have nevertheless been unable to get Sinema’s attention.

“Outside of calling her general office number, I don’t know how to get ahold of this woman,” Muir said, noting that she is in regular contact with Arizona’s other Democratic senator, Mark Kelly, who “has my cell phone number.”

“I follow her on Facebook, I follow her on Twitter, to kind of keep an eye on what’s happening, and I see a lot of her focus, and a lot of her energy, being spent on behalf of corporate interests [and not workers],” Muir added.

The Pima Area Labor Federation has demonstrated at both of their senators offices in recent weeks. Muir said that Sinema’s in Tucson, to her knowledge, is unoccupied. They want the lawmakers to commit to passing the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, a Biden-backed bill that would expand collective bargaining rights and set parameters for the classification of union-eligible workers.

The PRO Act passed the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives with some bipartisan support earlier this year and is now before the Senate, where it will need 60 votes to pass unless the filibuster is eliminated. But even if it is, Sinema and Kelly, along with Sens. Mark Warner of Virginia and Angus King of Maine, an independent who votes with the Democrats, are the only senators in their party who have not signed on as PRO Act cosponsors.

In early April, Sinema told the Arizona Chamber of Commerce and Industry at a virtual event that “many Arizona businesses have already reached out to my office” to discuss the PRO Act and she asked them to “please stay involved.” “The way I make decisions on behalf of Arizona, and for our constituents, is by listening to the business leaders who will be impacted by these decisions,” she said.

Two weeks later, the senator was a featured speaker at the National Restaurant Association’s annual public affairs conference, The industry group is one of the most vocal opponents of a $15 minimum wage.

Arizona is a newly minted swing state. In addition to Sinema’s 2018 victory, and Kelly’s in 2020, Biden was the first Democratic presidential candidate to win there since Bill Clinton in 1996. The state’s Democrats warned that Sinema needs to tread carefully, lest her focus on independent-leaning voters means she loses the support of the progressives who made the calls and knocked on doors.

In September 2019, Arizona progressives sought to censure Sinema at the Democratic Party’s quarterly meeting due to her failure to more forcefully reject then-President Donald Trump’s agenda. The measure failed. Jenise Porter, co-chair of the party’s progressive caucus, said: “If we were to do the same thing now, it might go differently.”

Recent polls show that Sinema’s politically conciliatory approach is likely costing her support among Democrats, though she is not up for reelection until 2024. Kelly, who won a special election in 2020 and will be on the ballot again next year, has ratings that are more favorable.

“I would say, never more than any other time in my 15 years in Arizona, have so many groups been working together to the same end, even groups that are more traditionally conservative, veteran’s groups, Latino groups,” Porter said.

“This is a coalition that was built not just to win an election but to change the state, and I think they will,” Porter added.

Porter said Sinema and her staff have provided “no response” to their coalition’s requests to discuss key issues.

This article first appeared at The 19th and is reprinted with permission.