It is arguably the most important single question in US politics today: How can the United States halt its downward spiral into extremism, gridlock and cross-partisan hatred?

For many advocates, a critical piece of the answer is the electoral reform known as ranked-choice voting. “It reduces the incentive to be divisive as a strategy,” says Anna Kellar, director of the League of Women Voters of Maine and a leader in the 2016 drive that got the reform adopted in that state.

In fact, it turns the incentives around, says Kellar: Because a ranked-choice system automatically transfers people’s votes to their second, third or later choice of candidates if their first choice loses, candidates are forced to treat everyone as a potential supporter. The result, hopefully, will be campaigns that reward bridge-building and broad appeal instead of attack ads, culture wars and exciting the base — and in the process, de-inflame our politics.

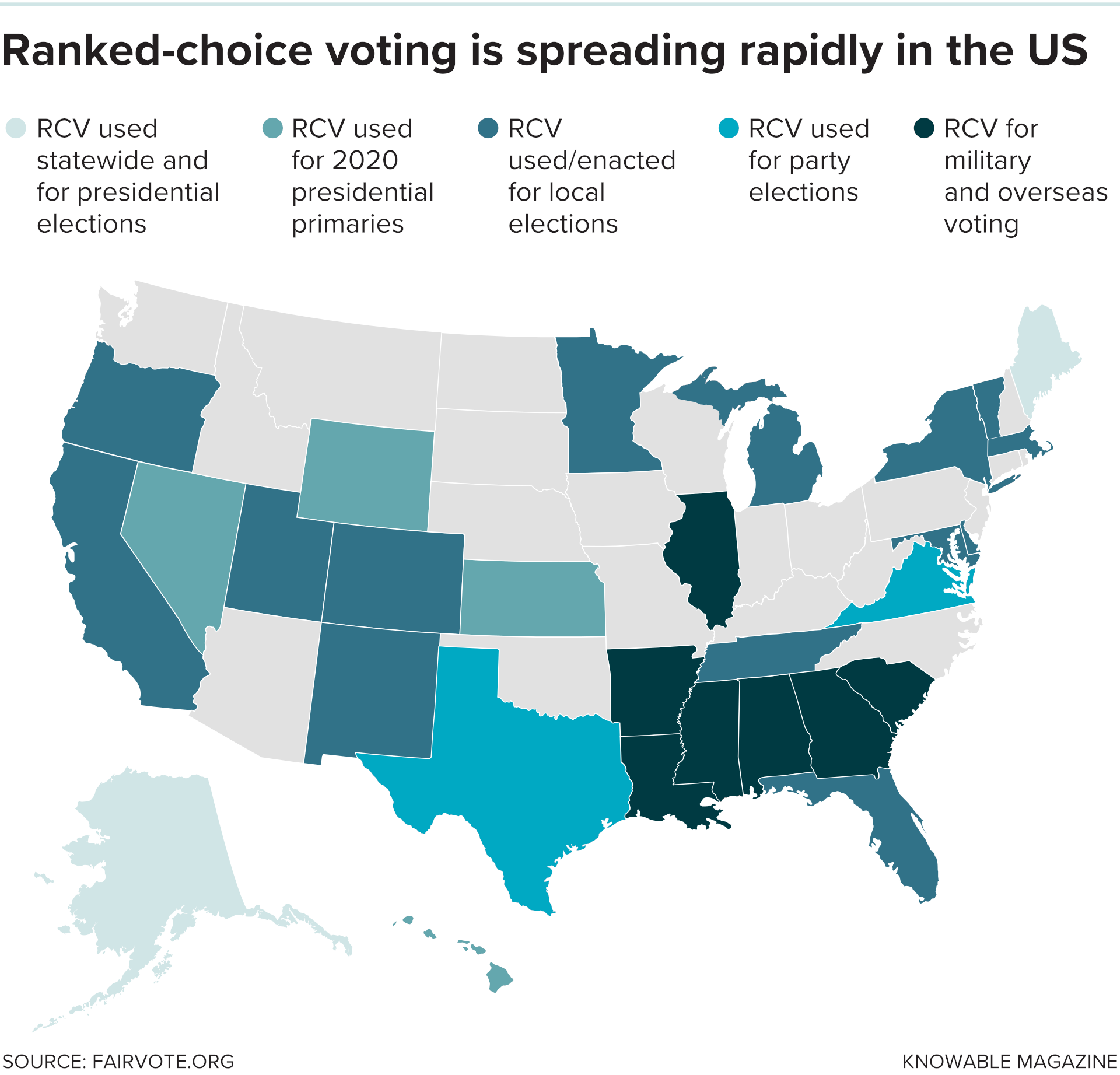

That hope is one big reason why US foundations, philanthropists and individual donors have been pouring money into ranked-choice reform efforts for the better part of a decade. And it’s why ranked-choice voting, also known as instant-runoff voting, has already been adopted in dozens of US cities and states. These early adopters range in political affiliation from the 23 cities in ruby-red Utah that will start using ranked-choice voting in November, to the independent-friendly states of Maine and Alaska, to Democratic bastions such as San Francisco and Berkeley — and now New York City, which became by far the most populous member of the group when it used ranked-choice voting for the first time in its June 22 mayoral primary.

Proponents have high hopes that this cross-partisan momentum will continue. “I think we’re going to see every jurisdiction using ranked-choice voting in 10 years,” declares Rob Richie, CEO of the ranked-choice research and advocacy organization FairVote.

Yet that is hardly a foregone conclusion. Ranked-choice voting still feels new and strange to most Americans, and poses a host of questions. How does it work, for starters? Is it too complicated for voters to understand? Can it actually deliver on its promises? And does it have any hope of surviving in the current political climate?

Here’s what we know so far.

Ranked-choice voting is neither new nor untried. The idea itself dates back at least to the 1850s, and it’s been used for national elections in Australia and Ireland for a century now. Its prime motivation — leaving aside, for the moment, the promise of calming political waters — is to solve a specific set of problems that exist with “plurality” voting: the familiar system that has long been the norm in the United States, the United Kingdom and many other countries.

Plurality voting does have the virtue of simplicity: Whoever gets the most votes wins. But in close races it is vulnerable to the kind of third-party spoiler effect made infamous in the 2000 US presidential election: The tiny fraction of votes that went to activist and Green Party candidate Ralph Nader in Florida almost certainly cost Democrat Al Gore the state and the presidency. Many jurisdictions try to get around this issue by holding a runoff election between the top two vote-getters. But runoffs tend to be time-consuming, expensive and — because turnout is usually abysmal — decided by a small fraction of the total electorate.

Even worse, plurality voting can produce winners that most voters don’t want: candidates who squeak into office only because two or more rivals split the opposition. Easily the most consequential recent example was the 2016 US presidential contest, when Donald Trump prevailed in the crowded Republican primaries with just 45 percent of his party’s vote. Another was the 2010 election of Maine Governor Paul LePage, a divisive, confrontational figure who won a four-way race with 38 percent of the vote. And had the September 14 recall effort against California Governor Gavin Newsom not been defeated, he would have been replaced by Republican Larry Elder – whose polling average on election eve was less than 30 percent.

Reformers often argue that examples like these aren’t anomalies — that the plurality system has increasingly turned negative campaigning and extremism into an effective campaign strategy. Get enough of your supporters excited, after all, and it doesn’t matter how many other voters you alienate: A non-majority win is still a win.

But the system can also undermine even the best winner’s legitimacy, says Jason Grenn, director of the ranked-choice advocacy organization Alaskans for Better Elections. When his state adopted ranked-choice voting in 2020, he says, Alaska hadn’t elected a US Senator with more than 50 percent of the vote since 2002. “It’s a tough message for a winner to say, ‘OK, I’m going to DC with 40 percent approval but 60 percent of my district didn’t support me,’” he says.

Ranked-choice voting is designed to solve all these problems by producing officeholders who have majority support. Here’s how it works:

First, voters are asked to rank the candidates by preference on election day, instead of choosing just one. (And no, you can’t leave middle rankings blank and mark your least-favored choice as last.) If the tally then shows that someone got more than half of the first-choice votes, as Republican Susan Collins did in Maine’s ranked-choice 2020 election for the US Senate, they win outright and everything proceeds as before.

But if no candidate gets more than half of the first-choice votes, the counting goes into instant-runoff mode: The candidate with the lowest total is eliminated — think Nader (and others) in the Florida 2000 example — and their votes are reallocated to their supporters’ second choices. This elimination process then repeats through as many rounds as needed, until one candidate passes 50 percent. New York’s crowded Democratic primary turned out to be a classic example: Candidate Eric Adams went from 30.7 percent of the vote in the first round to 50.4 percent and victory in the eighth.

The elaborate ranked-choice counting process is no problem for computers; most of the major voting-machine manufacturers now offer it as an option. But there’s long been a worry that the ranked-choice approach will seem incomprehensible to the voters themselves — especially those who are poorer, less educated or members of minority groups. If so, the reform would only end up deepening the inequities that already exist. Certainly, that charge was freely tossed around during the New York City primary campaign.

But academic studies tell a different story. In a 2019 paper comparing California cities that did and did not use ranked-choice voting, for example, political scientist Todd Donovan and his coauthors found that almost 88 percent of the respondents still rated the instructions as “easy” or “somewhat easy.” (Slightly more older voters in the ranked-choice cities did have trouble understanding the election system.) And more to the point, says Donovan, of Western Washington University in Bellingham, “we didn’t find any racial or ethnic differences.”

In 2021, University of Iowa political scientist Joseph Coll published similar results based on data from Alaska, Hawaii, Kansas and Wyoming, the four states that used ranked-choice voting for their 2020 Democratic presidential primaries. (They didn’t get much attention because now-President Joseph Biden was already the presumptive nominee.) And in an exit poll from this year’s New York City primary, 95 percent of the voters found the ballot simple to complete — and 77 percent said they wanted to use ranked-choice voting in future elections.

But the New York exit poll also showed that only 83 percent of the voters ranked two or more candidates. Although that number is quite a bit higher than in most other US elections using ranked-choice voting, it does illustrate another frequent criticism of the system. When voters aren’t required to rank all of the candidates (as they are for some races in Australia), their ballots can become “exhausted” and no longer count in later rounds of the tally.

And if enough ballots meet that fate, then it’s theoretically possible to produce a winner who doesn’t actually have support from a majority of voters.

It’s not clear how significant this exhausted-ballot problem is in practice. But the issue underscores how much the ranked-choice system is asking of voters: They’re supposed to form opinions about a whole list of candidates when they frequently have trouble picking even one. And it likewise underscores a broader point about ranked-choice voting. As Donovan puts it, “jurisdictions need to do some voter education to make it work.”

This was definitely a priority for Kellar’s group in Maine, both before and after their 2016 victory. “We held a whole bunch of events with our local breweries, where people could taste three or four of the beers and rank them in their order of preference,” says Kellar. “And then we would go through the rounds to see which beer would be good for the majority of people, and show the counting process in a way that people understood.” The group did similar exercises at county fairs using pizza and ice cream, and even made a video of people dressed up as ballots, moving around to show how the rounds worked.

“Somebody tries to explain ranked-choice voting to you in words and it sounds like the most complicated thing ever,” says Kellar. “But if you do it with ice cream, people realize that ranking is something that we do every day.”

Will ranked-choice voting really heal political divisions? Maybe. Ranked-choice campaigns certainly seem less negative, according to a 2016 survey that Donovan coauthored with University of Iowa political scientists Caroline Tolbert and Kellen Gracey. And this perception of heightened civility was confirmed in a novel way this year, when political scientist Martha Kropf of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte published an analysis of Twitter comments and newspaper stories about ranked-choice contests. Kropf found that the ratio of positive to negative words in news stories was significantly higher than in regular elections.

This heightened civility, along with decreased concerns about acting as a spoiler, may in turn make ranked-choice campaigns feel more welcoming to women or minority candidates: Studies show that the system is generally not a barrier for them, and in some cases may even have boosted their chances.

Still, says Benjamin Reilly, a political scientist who studies voting systems at the University of Western Australia in Perth, the ranked-choice approach doesn’t automatically make people nicer. Even after a century of it in Australia, he says, “we have a highly adversarial system with all the usual theater of politicians shouting at each other.” There were also plenty of verbal punches thrown in Maine’s 2020 Senate campaign, and in this year’s New York primary.

But ranked-choice voting’s promise of reducing division and extremism is quite real, says Reilly; he found compelling evidence for the effect with his thesis work in Papua New Guinea.

“The place is extremely fragmented along ethnic lines, with all these micro-clans and tribes,” he says. Yet back in the 1960s, when the area was under Australian colonial administration and used its ranked-choice rules, elections were surprisingly civil. “The studies from that period all talked about how there were these deals being done between tribal and clan groups to get second votes” from one another’s supporters, Reilly says.

But with independence in 1975, he says, Papua New Guinea adopted US-style plurality voting instead. By the time Reilly started his research there in the 1990s, he says, “the incentives to do deals and trade-offs had completely disappeared. People were winning elections with five and six percent of the vote, because there were 60 candidates standing sometimes.” And with officials taking office with almost no support, he says, “that was leading to a lot of tribal violence, and other problems.”

Things calmed down a bit after 2003, when Papua New Guinea went back to ranked-choice voting and the deal-making reemerged. It remains a deeply troubled country, says Reilly, who has found comparable alliance-building in Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Fiji and other divided regions that have adopted ranked-choice voting. “But it was a really interesting natural experiment of what can happen under two different electoral systems.”

Similar, if less dramatic, alliances have already started popping up in Maine, San Francisco and other US ranked-choice jurisdictions. A particularly well-publicized example came late in the New York primary campaign, when candidates Andrew Yang and Kathryn Garcia seem to have tried to counter front-runner Adams by appearing together, with Yang asking his voters to rank them first and second.

It didn’t work: Adams won anyway. But even so, says Richie, look for more such collaborative campaigning as politicians get used to the logic of ranked-choice voting. In his own town of Takoma Park, Maryland, where it’s been used since 2007, “I’ve seen candidates walk past a yard sign for their opponent and knock on the door to talk to someone anyway,” he says. Getting one more second-choice ranking can matter.

That said, however, there remains one crucial question that only time can answer.

Can ranked-choice voting survive in the United States? There is still ample reason for skepticism on that score — not least because ranked-choice voting has already failed here once. Versions of the system were used for local elections in some two dozen US cities during the first half of the 20th century, only to be repealed almost everywhere as party bosses fought back against their loss of control. By 1962, the sole survivor was Cambridge, Massachusetts; it would stand alone until 2004, when San Francisco became the first city in the modern era to start routine use of ranked-choice voting.

The current wave of adoptions hasn’t always gone smoothly, either. In 2020, for example, Massachusetts voters rejected ranked-choice voting by close to a 10-percentage-point margin. “Voters didn’t see a clear problem it was solving, says Tyler Fisher, senior director of policy and partnerships at Unite America, a Denver-based nonprofit that supports a variety of electoral reforms.

Then, too, today’s revival of ranked-choice voting comes at a time of profound mistrust in our election system in general — by both sides.

In New York, for example, when Eric Adams denounced the Yang-Garcia alliance as an attempt to undermine candidates of color like him, he was reflecting a widespread worry that ranked-choice voting would harm minority representation. That accusation could have become incendiary indeed if Garcia had edged past Adams in later rounds, as she almost did.

And substantial portions of the right still denounce ranked-choice voting as some kind of leftist plot. According to a 2019 report on ranked-choice voting from the Heritage Foundation, a prominent hard-right think tank, “So-called reformers want to change process rules so they can manipulate election outcomes to obtain power.”

Yet opponents can be persuaded. In Utah, for example, lobbyist and lifelong Republican Stan Lockhart remembers being a skeptic back in 2002, when his party first used ranked-choice voting in its state nominating convention. But by 2017, when advocates asked if he would help them take the reform statewide, he took the job as an ardent convert.

What helped change his mind, says Lockhart, who now works through the nonpartisan advocacy group Utah Ranked Choice Voting, was seeing the reform’s effects on his own party. “We had less infighting, less attacking one another, less politics of personal destruction, and more focus on issues,” he says. “I liked that. There was the opportunity for a candidate to get a majority of support. I liked that.”

And, says Lockhart, “I liked that a voter got to more fully express their will.”