The canard that the “real” reason people leave Christianity is to embrace a “life of sin” is an old standby in the apologist’s bag of tricks. Even Russell Moore, perhaps the most visible ‘respectable’ evangelical, falls back on it at times, writing recently that “the desire for sexual hedonism” is a contributing factor to the exodus of young people from evangelical churches, even while mildly pushing back against those who suggest it’s the primary or only reason for the youth’s secularization.

Some conservative Christian pastors, even ‘respectable’ ones like Tim Keller, who claims that sex outside straight Christian marriage is “dehumanizing,” treat the accusation that “sex is the real reason you left” as the ultimate gotcha. While the trope is far from new, it seems to me that evangelicals are invoking it with increasing frequency these days, almost certainly as a peevish response to the visibility of exvangelicals, who are increasingly gaining a hearing for our own perspectives on why we left evangelicalism–whether for a more accepting and inclusive version of Christianity, some other religion or type of spirituality, or nonreligion. Loss of control over the narrative of leavers is a massive threat to evangelicals’ egos and their hold on power and influence, and so they’re doubling down on pernicious stereotypes.

That being said, the suggestion that sex plays a role in the deconstruction of authoritarian Christianity is not entirely incorrect, though things hardly ever play out in real life as they do in the fevered imaginations of Christian apologists. I, of course, cannot speak for every exvangelical or other former conservative Christian. The reasons people leave are manifold. It’s hard for me to imagine anyone leaving for just one reason, and it’s also true that we humans are not always aware of our motivations. Some people who leave high-control religious groups, or religion altogether, cite intellectual motives, and many historically orthodox Christian beliefs are indeed intellectually untenable.

Many people also have ethical objections to conservative Christian teachings that may or may not directly affect them–that it is a “sin” to be gay or transgender, for example. On that count, we cannot ignore the fact that extreme rigidity on matters of sex, sexuality, and gender roles–as seen, for example, in evangelical purity culture, on which Linda Kay Klein’s work is indispensable–is damaging to everyone who is socialized in it, and especially damaging to women and LGBTQ folks. With that in mind, we need to flip the script.

Instead of accepting that leaving a high-control form of Christianity to potentially pursue greater sexual freedom is somehow contemptible, we should focus on patriarchal Christianity’s longstanding and extremely unhealthy obsession with sex. From that vantage point, we can see that the Christians who make literally everything about sex are the real problem. That being the case, it is only natural that matters related to sex, sexuality, and gender are going to be important to the deconstruction of the faith.

Sigmund Freud may be rather out of vogue these days, and to be sure, not everything the founder of psychoanalysis posited has withstood the test of time. For example, Freud’s reduction of the multifaceted, complex phenomenon of religion itself to the projection of the human need for a strong father figure is something no serious scholar of religious studies would accept today. Nevertheless, research in cognitive science has empirically demonstrated a link between the kind of paranoid authoritarianism that characterizes the Christian Right, and devotion to a strict patriarchal family structure. That structure serves as a foundational metaphor for authoritarian politics and it is also reflected in conservative Christian attitudes toward sex, sexuality, and gender.

Whatever he might have gotten wrong, Freud was undoubtedly correct that many human behaviors and pathologies are rooted in sexuality and its attendant anxieties. Observing Christianity provides us with a wealth of obviously relevant examples of such phenomena as projection and the return of the repressed. Yes, to be sure, “not all Christians,” but there is a consistent influential thread of sexual paranoia that runs through Christian history from the very beginning.

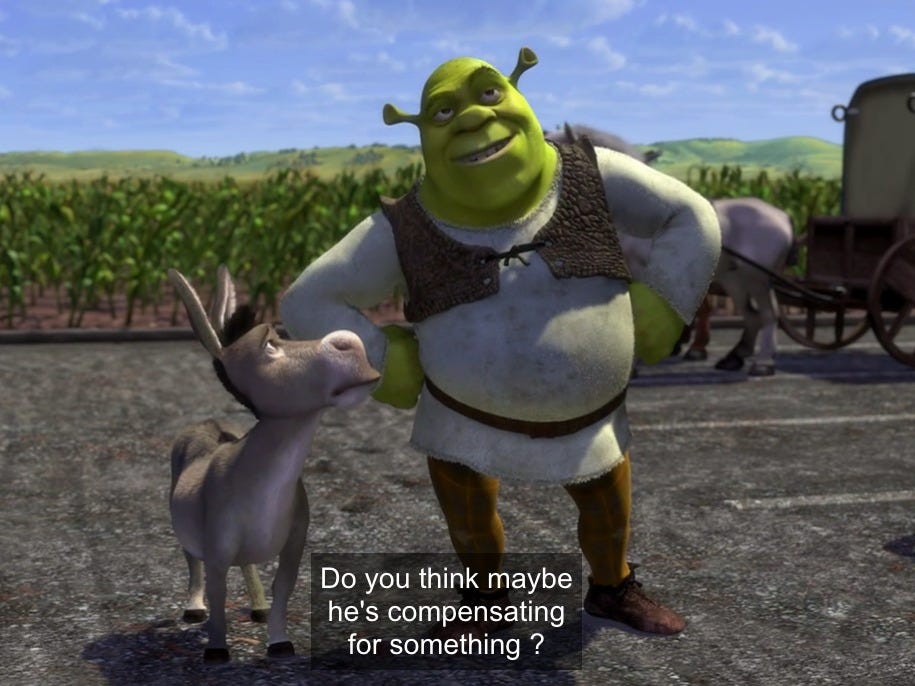

For example, sociologists Samuel L. Perry and Andrew L. Whitehead have found that “the preponderance of evangelicals in a state consistently predicts more Google searches for terms and phrases like ‘male enhancement,’ ‘ExtenZe,’ ‘penis pump,’ ‘penis enlargement,’ and others.” These scholars, known best for their work on Christian nationalism, suggest that the reason evangelical men engage in such Google searches is “that the largely patriarchal―and increasingly embattled and radicalized―evangelical subculture explicitly or implicitly promotes equating masculinity with physical strength and size.”

When it comes to conservative, mostly white evangelical men, the meme that Rick Pidcock tweeted appropriately at infamously penis-obsessed Pastor Mark Driscoll the other day is evergreen:

Meanwhile, conservative Christian sexual paranoia leads to repression and intense anxiety that, particularly among men raised both to assert their masculinity and to fear their sexual urges (and the women they blame for them), is sometimes externalized as violence. This seems to be the case for the Atlanta massage spa murderer, whose strict evangelical background is relevant context for his attempt to blame his racist, misogynistic, and anti-sex-worker rampage on his supposed “sex addiction.” (There is no consensus among experts, it should be noted, on the validity of sex addiction and porn addiction as diagnoses, and, of course, neither is a valid defense for murder.)

A similar dynamic was in play when James Dobson, the anti-LGBTQ and enthusiastically pro-spanking psychologist who founded Focus on the Family, interviewed serial killer Ted Bundy just before the latter’s execution, giving Bundy the space to profess remorse while placing the blame for his brutal rapes and murders on exposure to pornography. In this connection, one might also note that the notorious Proud Boys, some of whom prayed an unmistakably evangelical prayer just before storming the Capitol on January 6, forbid their members from masturbating more than once a month and from viewing pornography. The cutting-edge research on Christianity and pornography carried out by Joshua Grubbs, the son of a Southern Baptist preacher and an associate professor of psychology at Bowling Green State University, helps to shed light on the attitudes and anxieties in play in these situations.

I’ve interviewed Grubbs a few times, and in one of those interviews, he described how some people “feel out of control” even if their porn consumption is minimal. “For these people,” says Grubbs, “who may only be using pornography less than once a week, the best predictor of whether or not they report feeling ‘addicted’ to pornography is whether they morally disapprove of pornography use.” Such moral disapproval is usually grounded in religion, and it may lead to self-hatred for people who are ashamed of their own desires. More recently, when I asked Grubbs to comment on the Atlanta spa murders, he noted:

There’s a large and growing body of research that shows that conservative religious values are strongly linked to feelings of sex addiction. We find that men in particular are likely to interpret normal sexual urges as pathological and then act on them in ways that they find to be problematic.

At the same time, however, given the intensely patriarchal nature of conservative Christianity, men perceived as straight are often offered protected from accountability for their transgressions–even when those transgressions constitute crimes. In evangelical subculture, boys are taught that their sexual urges are essentially uncontrollable, while the onus is placed on girls not to “tempt” the boys (and adult men). Meanwhile, the flattening of all “sexual sin” into a single category in which consent does not come into play–pedophilia, consensual queer sex of any kind, viewing porn, and consensual straight sex outside of marriage are all seen as equally sinful in God’s eyes–opens the door for the uneven application, and even weaponization, of concepts like authority, repentance, forgiveness, grace, and justice. Those who are perceived as “sexually deviant” are often the ones singled out for the punitive application of “justice,” and women and children who are victimized by powerful men are often coerced into performing a type of forgiveness that shields the abuser from serious repercussions. Meanwhile, prohibitions on “gossip” serve to protect the existing power structures.

Reality TV’s famous Duggar family provides an excellent case in point. When a teenage Josh Duggar molested several much younger girls, his parents, Jim Bob and Michelle Duggar, worked to cover up the abuse and to protect their son from facing any real consequences for his criminal actions. At the same time, they were actively engaged in political opposition to transgender rights, because, while “good Christian boys” deserve consequence-free forgiveness, LGBTQ folks make convenient scapegoats on which to project evangelicals’ sexual shame and anxiety. Never mind that the “problem” of trans women engaging in predatory behavior in women’s bathrooms is entirely imaginary. When the news of Josh’s molestation of young girls did come out, two of the Duggar sisters he had victimized made a show of publicly forgiving him. Given all this, we really shouldn’t be surprised by the fact that Josh has recently been arrested on charges of downloading and possessing child sexual abuse material that one federal agent described as some of the worst he’s seen.

Wherever extreme paranoia about sex and gender manifest in vigorous efforts to police the bodies and curtail the rights of queer people, women, and children, you can be confident that those who shout the loudest likely have skeletons in their own closets. And, as more and more evangelical abuse scandals have broken over the last few years, I have become ever more confident that child sexual abuse is every bit as rampant in evangelicalism as it has infamously been reported to be in the Catholic Church. This too, should be unsurprising, given that the Christian sexual paranoia that fuels such abusive dynamics is as old as Christianity itself.

The original missionary busybody, Paul, protested a bit too much about the various forms of “sexual immorality” in his epistles, in my view. In I Corinthians, Paul tells us in a passage condemning “fornication” that we “are not our own” but were “bought with a price,” i.e., Christ’s death, piling on the guilt and leaving little room for human autonomy, whether in sexual matters or anything else. In the same book, he argued that it is best for Christians not to marry, while allowing that “it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion,” thereby laying the foundation for the ascetic practice of celibacy in Christianity. In light of what we now know about the prevalence of child sexual abuse perpetrated by “celibate” authority figures in Catholic institutions, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the “calling” of ascetic celibacy has been anything other than an immensely destructive force in the history of Christianity.

We may not have Paul to “thank” for the widespread Christian belief that God wants wives to submit to their husbands, who, according to the author of the epistle to the Ephesians, are the heads of their wives, just as Christ is the head of the church. Many scholars dispute Paul’s authorship of the work, but even so, the authority of Paul’s name was used to establish this misogynistic doctrine from the early days of the faith.

And speaking of misogyny, any assessment of unhealthy attitudes toward sex and gender in Christianity, however brief, would be remiss not to mention Augustine, the fourth-century Bishop of Hippo who dedicated about a decade and a half to writing a treatise on why the book of Genesis should be read as literally as possible. Why was that so important to this obsessive man, who, as his Confessions clearly indicates, was deeply afraid of his own libido? As Stephen Greenblatt explains in a fascinating essay, Augustine needed a literal Adam and Eve in order to justify his belief that original sin was passed down through the corrupting involvement of lust in the process of reproduction.

In Augustine’s view, in Eden, it would have been possible for Adam and Eve to have sexual intercourse for the purpose of reproduction without lust, thus populating the world sinlessly. Unfortunately, the first humans ate of the forbidden fruit and at once became conscious, and ashamed, of their genitals, which would now fulfill their reproductive function only in the presence of sinful, sinful lust. According to Augustine, this ensured that the curse of their fallen nature would be passed down to every human child. Except, of course, Jesus, who, Augustine posited, was conceived immaculately, since he was conceived without the involvement of a human father and born of a virgin.

Interestingly, because the branches of early Christianity that became the Eastern Orthodox churches don’t fully embrace Augustine’s dark view of human nature, he is not considered a saint in Eastern Orthodoxy, but only “blessed.” Nevertheless, a strong thread of sexual paranoia still runs through the Orthodox Churches, as a quick glance at post-Soviet Russia will confirm. The very politically active Russian Orthodox Church currently supports the decriminalization of domestic violence, any and all state-sponsored assaults on the LGBTQ community, and the corporal punishment of children. In addition, Russian conservatives are heavily involved in international efforts to promote “the natural family” by depriving women of bodily autonomy and queer people of any civil rights.

Given the unhealthy and destructive sexual paranoia that pervades most of Christianity, past and present, it should be no surprise that sex often plays a role in the deconstruction of conservative Christianity. Indeed, it would be surprising if it did not. And now, against that background, I would like to share some of my own story of being traumatized by evangelical purity culture, the rejection of which was a factor, though not the only factor, in the trajectory that ultimately led me to atheism.

As far back as seventh grade, when my entire class at Colorado Springs Christian School was taken on a “retreat” where we were given disinformation about condom failure and told not to “cheat on our future spouses” by doing anything with a girlfriend or boyfriend that we wouldn’t do with someone else’s husband or wife, I began to feel that all the fear-mongering and shaming about sex was manipulative. At the end of that day I, like presumably everyone else present, signed a purity pledge after sitting for a few moments “in prayerful consideration.” It occurred to me that I might be expelled if I refused to sign it–how was I to know?–and that the whole thing was thus coercive. Neither then, nor in high school, however, did I reject the belief that sex should be “saved for marriage”; I only objected quietly to the manipulative means of delivering that message to children.

The first time I was convinced I had committed “the unpardonable sin”–and thus would be tortured eternally in hell no matter what I did from that point in my life–it was because I had broken a promise to God to stop masturbating. Surely, if anything constituted the obscure category of “blasphemy against the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 12:31-32), it was the breaking of a vow made to God, right? I was about 16 and about as horny as most people that age; in retrospect, making that vow was obviously a terrible idea. At the time, however, I believed I was acting out of the “conviction” of the Holy Spirit.

Between awkward talks with my dad and reading Preparing for Adolescence by James Dobson, I had previously gotten the idea that masturbation was sort of a gray area–not necessarily a sin, if one’s engagement in the practice was strictly “mechanical.” (Looking back on this now, of course, I detect an echo of Augustine in my thinking.) On the other hand, “lustful thoughts” were clearly a sin according to Jesus (Matthew 5:27-28), and Paul had given Christians the very anxiety-inducing directive to “take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ” (I Corinthians 10:5). And since I–a teenager steeped in evangelical purity culture–found it impossible to decouple masturbation from “lust” and sexual fantasy, I figured I should just give up self-pleasuring. Believing, in my practically boundless naivete, that God would give me the fortitude to keep my promise, I vowed to refrain from any further fapping–ever. I figured I’d have sex when I was married and would no longer want to masturbate at that point anyway.

Predictably, I failed a week or two later. As I’m now in my early forties, my memories from that time in my life can get a little fuzzy and jumbled, but there is one thing I remember very clearly–the palpable lump of anxiety I carried around my chest for the next week or so, during which nothing could take my mind off my impending eternal damnation. Thankfully, a man I’d sought out for advice because I believed him to be very “spiritual,” one of my teachers at Heritage Christian School in Indianapolis, from which I graduated in 1999, eventually convinced me that the fact that I wanted to repent meant that it was still possible for me to repent. Therefore, I had not blasphemed the Holy Spirit.

To give readers a sense of just how bonkers my evangelical milieu was, I’ll note that this same high school chemistry, physiology, AP biology, and AP chemistry teacher, Mr. Terry, predicted the Rapture for “probably sometime this fall around Yom Kippur” to his students. In class. Both years I had him as a teacher. Nothing really happened when he turned out to be wrong. I mean, he had said “probably,” and clearly we were living in the last days. Right? According to more recent alumni I’ve talked to, at least Mr. Terry still believes so.

In high school, while I remained committed to maintaining “sexual purity,” my intellectual doubts about Christianity grew. I read through the entire Bible for the first time, and I began to find it impossible to ignore the contradictions. My ethical qualms over divinely sanctioned genocide and sending people to hell for eternity simply for “believing the wrong things” also gnawed at me. As a cerebral kid who had long since learned to live in my head as a coping mechanism for always somehow feeling “different” from those around me and uncomfortable in my own skin, I fixated on these intellectual problems.

Having recalled this history, I suppose that I began deconstructing my faith as a teenager, but it was a very protracted and painful process for me–one that was not only about sex and gender, and that might have been sped along if there had been any sort of visible exvangelical community in the 1990s. My internalized Christian paranoia about sex caused me a great deal of psychological distress into my twenties, and my first partnered sexual experiences were accompanied by intense guilt and crying afterwards.

At this point, conservative Christian readers may be thinking, “Aha! You were convicted by the Holy Spirit.” But it’s Christians like them who subjected me to years and years of systematic shaming in order to program me to feel the way I did. It’s curious, to say the least, that they seem to think the Holy Spirit needs so much help. (Perhaps, if actions speak louder than words, sex-obsessed evangelicals don’t really believe in the conviction of the Holy Spirit? Well, who’s the blasphemer now, hm?)

In these years, I still didn’t want to rock the boat with my family. I tried as hard as I possibly could, for as long as I possibly could, to hold on to a kind of Christianity that would be recognizable to them, but the effort was literally killing me. I experienced near daily suicidal ideation in those years of willing myself to repress my authentic self, and I repressed so much of myself so well that it took me until I was 33 years old to realize that I was queer. Such delayed recognition of queerness seems to be common among those raised in high-control, sexually obsessive Christian environments. In retrospect, it seems to me that my agonizing intellectual deconstruction was so drawn out in part because it was serving as a proxy for my need to address my unrecognized gender identity, which I simply didn’t have the intellectual tools necessary to conceptualize until I was in my 30s.

That admission is probably enough for someone like Tim Keller to dismiss my rejection of Christianity as “merely” about all that sweet, sweet sex and other “sin,” but it was always so much more than that–and a big part of it was my growing sense that the Christian beliefs I had been taught about hell as eternal conscious torment and about queerness being “sinful” were themselves abusive. I stand by that. For what it’s worth, I’ve still had only a handful of intimate partners, and I haven’t had partnered sex in years. But even if I were having sex all the time, as so many pastors seem to imagine, you know what? My rejection of Christianity would be just as valid, and their attitudes toward sexuality and gender would remain just as immensely destructive.

At this point, they have subjected multiple generations of American kids to extreme Christian schooling and homeschooling, which is a powerful means of indoctrination in purity culture. It instills in children a toxic combination of obsession with the idea of sex and a slew of unrealistic beliefs about it–beliefs like, for example, that after many long years of repressing sexual desire, one can get married and suddenly just have satisfyingly awesome sex with no hangups. The sexual repression and attendant anxieties that come from being raised in a high-control Christian environment cause long-term damage, and Christianity’s “sin”/”not sin” (as opposed to consensual vs. nonconsensual) framing of sex generates conditions in which powerful male abusers are unlikely to be held accountable and unhealthy sexual acting out is normalized, as is the projection of conservative Christians’ sexual anxieties onto sexual and gender minorities, which sometimes results in horrific violence.

So, then, is the exodus of young people from conservative Christianity really about sex after all? While sex alone certainly does not explain the emptying of the pews, and the personal significance of sex in individuals’ deconstructive processes will vary, how could deconstructing the ideology that leads people to participate in aggressive protests in front of clinics that provide medically necessary abortions not be about sex on some level? The next time some arrogant apologist pulls out the “You just wanted to have sex” line, remember that it’s the sexual paranoia that right-wing Christians inflict on children and converts that make the reconsideration of sex, sexuality, gender identity, and the politics around them an inevitable part of leaving conservative Christianity.

Conservative Christians are the ones insisting on the divine sanction of demonstrably destructive attitudes about sex. Rejecting those attitudes is a healthy, positive step for both individuals and society.